Resolve (January 1966-June 1967)

Episode 4 | 1h 57m 25sVideo has Audio Description

US soldiers discover Vietnam is unlike their fathers’ war, as the antiwar movement grows.

Defying American airpower, North Vietnamese troops and materiel stream down the Ho Chi Minh Trail into the south, while Saigon struggles to “pacify the countryside.” As an antiwar movement builds back home, hundreds of thousands of soldiers and Marines discover that the war they are being asked to fight in Vietnam is nothing like their fathers’ war.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Funding for The Vietnam War is provided by Bank of America; Corporation for Public Broadcasting; David H. Koch; The Blavatnik Family Foundation; Park Foundation; The Arthur Vining Davis Foundations; The...

Resolve (January 1966-June 1967)

Episode 4 | 1h 57m 25sVideo has Audio Description

Defying American airpower, North Vietnamese troops and materiel stream down the Ho Chi Minh Trail into the south, while Saigon struggles to “pacify the countryside.” As an antiwar movement builds back home, hundreds of thousands of soldiers and Marines discover that the war they are being asked to fight in Vietnam is nothing like their fathers’ war.

See all videos with Audio DescriptionADProblems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch The Vietnam War

The Vietnam War is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Buy Now

Vietnam Stories

We asked viewers to share their experiences during the events of the Vietnam War era. The response was thousands of videos, photographs, and short stories.Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipMore from This Collection

These episodes feature audio tracks containing English, Spanish and Descriptive Audio.

The Weight of Memory (March 1973-Onward)

Video has Audio Description

Saigon falls and the war ends. Americans & Vietnamese from all sides seek reconciliation. (1h 50m 56s)

The Veneer of Civilization (June 1968-May 1969)

Video has Audio Description

After chaos roils the Democratic Convention, Nixon, promising peace, wins the presidency. (1h 50m 54s)

This Is What We Do (July 1967-December 1967)

Video has Audio Description

President Johnson escalates the war while promising the public that victory is in sight. (1h 28m 17s)

Things Fall Apart (January 1968-July 1968)

Video has Audio Description

Shaken by the Tet Offensive, assassinations and unrest, America seems to be coming apart. (1h 27m 46s)

The River Styx (January 1964-December 1965)

Video has Audio Description

With South Vietnam near collapse, LBJ bombs the North and sends US troops to the South. (1h 57m 55s)

Video has Audio Description

As a communist insurgency gains strength, JFK wrestles with US involvement in Vietnam. (1h 26m 27s)

The History of the World (April 1969-May 1970)

Video has Audio Description

Nixon withdraws troops but upon sending forces to Cambodia the antiwar movement reignites. (1h 52m 9s)

A Disrespectful Loyalty (May 1970-March 1973)

Video has Audio Description

South Vietnam fights alone as Nixon and Kissinger find a way out for America. POWs return. (1h 52m 32s)

Video has Audio Description

After a century of French occupation, Vietnam emerges independent but divided. (1h 25m 20s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorshipANNOUNCER: MAJOR SUPPORT FOR "THE VIETNAM WAR" WAS PROVIDED BY MEMBERS OF THE BETTER ANGELS SOCIETY, INCLUDING JONATHAN AND JEANNIE LAVINE, DIANE AND HAL BRIERLEY, AMY AND DAVID ABRAMS, JOHN AND CATHERINE DEBS, THE FULLERTON FAMILY CHARITABLE FUND, THE MONTRONE FAMILY, LYNDA AND STEWART RESNICK, THE PERRY AND DONNA GOLKIN FAMILY FOUNDATION, THE LYNCH FOUNDATION, THE ROGER AND ROSEMARY ENRICO FOUNDATION, AND BY THESE ADDITIONAL FUNDERS.

MAJOR FUNDING WAS ALSO PROVIDED BY DAVID H. KOCH...

THE BLAVATNIK FAMILY FOUNDATION...

THE PARK FOUNDATION, THE NATIONAL ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES, THE PEW CHARITABLE TRUSTS, THE JOHN S. AND JAMES L. KNIGHT FOUNDATION, THE ANDREW W. MELLON FOUNDATION, THE ARTHUR VINING DAVIS FOUNDATIONS, THE FORD FOUNDATION JUSTFILMS, BY THE CORPORATION FOR PUBLIC BROADCASTING, AND BY VIEWERS LIKE YOU.

THANK YOU.

Announcer: Can looking back push us forward?

Man: Ladies and gentlemen, Miss Billie Holiday.

♪ Will our voice be heard through time?

Can our past inspire our future?

...act of concern... ♪ Bank of America supports filmmakers like Ken Burns, whose narratives illuminate new perspectives.

What would you like the power to do?

Bank of America.

JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: Sometimes I would hear a car crunch up in the snow, and I'd think maybe it would be somebody coming to give us bad news.

Which was not good for me to think.

It was an underlying anxiety that I really think was there all the time.

NARRATOR: All his young life, Denton Crocker, Jr.-- known as "Mogie" to his family-- had dreamed of serving his country, of putting his own life on the line in defense of what he called "individual freedom."

He'd wanted to serve in Vietnam so much he'd pressured his parents into granting their permission for him to join the Army before he was 18.

He was eager for combat and pleased when he was assigned to the 1st Brigade of the celebrated 101st Airborne, the "Screaming Eagles" who had led the way on D-Day.

But he was quickly disappointed to find himself attached to battalion headquarters, repairing weapons, making lists, keeping records.

It was "boring," he wrote home.

MOGIE CROCKER (dramatized): I think perhaps you will understand my disappointment when you see that there is little sense in being over here unless one faces the main objective, the destruction of the VC.

Certainly one feels no sense of accomplishment when one's friends are facing all the dangers.

JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: I had a map on the back of the living room door.

And I put pins in it every time Denton Jr. moved.

And he moved a lot.

And I knew those names at one time as well as any area of our own world.

LYNDON JOHNSON: Well, how'd you have a good weekend?

ROBERT McNAMARA: (laughs) Yeah, I did, Mr. President.

I hope you did too.

JOHNSON: What's your thinking these days?

I haven't talked to you.

What's happening to our pause?

What are our generals saying?

McNAMARA: See, I think you'll find some foreign leaders will criticize you if you resume bombing.

As a matter of fact, no other intelligence source that I've seen indicates that Hanoi is even considering moving toward negotiation in order to lead us to extend the pause.

Intelligence information... NARRATOR: As 1966 began, the president of the United States was just learning the name of the man who was the most powerful member of the Politburo in Hanoi-- Le Duan.

McNAMARA: ...First Secretary of the Communist Party, a man named Le Duan-- L-E capital D-U-A-N-- who today is putting considerable pressure on Ho Chi Minh and others to ensure continuing a war that he thinks they either are winning or can win.

("Masters of War" by The Staple Singers playing) ♪ They're masters of war ♪ ♪ You build all the big guns ♪ ♪ You build the big planes.

♪ NARRATOR: As they continued to escalate the war, Johnson and McNamara were frustrated that American commanders in Vietnam, who had come of age during World War II and Korea, were having a hard time making sense of what was happening on the ground.

In the months and years to come, as the American presence grew, Hanoi would escalate too, sending more and more soldiers south, strengthening its own air defenses, and recruiting more fighters from the alienated South Vietnamese countryside.

The Johnson administration was desperately trying to prop up the government in Saigon and, at the same time, help that government to somehow win the loyalty of its own people.

Johnson had tried to forge an international coalition to defend South Vietnam.

But only five other countries would ever send combat troops-- Australia and New Zealand, Thailand, the Philippines, and South Korea.

America's most important allies, Britain, France and Canada, refused to take part and were calling instead for peace talks.

And more and more Americans, including some of the country's most respected foreign policy experts, were beginning to question the way the war was being fought, whether it could ever be won, and if the United States should be in Vietnam at all.

(explosion) As 1966 began, 2,344 Americans had died in Vietnam.

Nearly 200,000 were stationed there, and more were on their way.

Those soldiers would quickly discover that the war they were being asked to fight was not their father's war.

SAM WILSON: We tend to fight the next war in the same way we fought the last one.

We are prisoners of our own experience.

And many of the things that we learned that worked in World War II were not applicable to the war in Vietnam.

We simply thought we'd go in with a sledgehammer and knock things down, clean them up, and it would be all over.

It was a kind of an oversimplification of the problem combined with our overconfidence that caused us, I think, to be arrogant.

And it's very, very difficult to dispel ignorance if you retain arrogance.

STAPLES SINGERS: ♪ I'll stand over your body and make sure that you're dead.

♪ (gavel pounding) NARRATOR: In early February of 1966, President Johnson got more bad news.

His old friend, J. William Fulbright, the powerful chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, planned to hold hearings on the Vietnam War, and the television networks intended to cover the hearings from gavel to gavel.

Fulbright, who had once supported the war, now opposed it.

LBJ was alarmed.

His own advisers had been giving him conflicting advice about Vietnam for years.

But a public debate about how he was running the war in front of millions of Americans filled him with dread.

As the hearings got underway, the president tried to deflect attention by suddenly announcing he was going to a military conference in Honolulu, to meet for the first time the two generals who now headed the Saigon government.

ED HERLIHY: It is a meeting without precedent, and is designed to strengthen United States determination to pursue to the end the drive against communist domination in South Vietnam.

NARRATOR: General Nguyen Van Thieu was the chief of state, but real power lay with Thieu's bitter rival, the former head of the South Vietnamese Air Force, Prime Minister Nguyen Cao Ky. Ky was "an unguided missile," according to one U.S. diplomat, known for his flamboyant uniforms, his gaudy private life, and his public pronouncements.

He once told a reporter that what Vietnam really needed was "five Hitlers."

PHAN QUANG TUE: How could we allow and accept that to happen?

He was a charlatan.

The man not only has no training, has no education, but doesn't seem to inter... be interested in being educated, and proud of his ignorance.

TRAN NGOC CHAU (speaking English): (laughing) NARRATOR: President Johnson spent most of his time in Honolulu urging Ky to focus on pacification-- earning the support of the South Vietnamese people by undertaking economic and social reforms Americans had been calling for for more than a decade.

Johnson wasn't interested in "high-sounding words" about progress, he said.

He wanted genuine achievements-- what they called in Texas, "coonskins on the wall."

BUI DIEM: Well, nobody understood what does it mean "coonskin."

And people the Vietnamese at the delegation they ask me, "You understand what it is?"

And myself I said, "Well, I don't understand."

I have to ask some Americans to explain to me.

And some American friends, they explain to me later on and only by then the Vietnamese understood.

I happen to hold the point of view that it isn't going to be too long before the American people, as a people, will repudiate our war in Southeast Asia.

MAXWELL TAYLOR: That, of course, is good news to Hanoi, Senator.

MORSE: Oh, I know that that's the smear artist that you militarists give to those of us that have honest differences of opinion with you.

But I don't intend to get down in the gutter with you and engage in that kind of debate, General.

NARRATOR: Johnson's trip to Honolulu had not distracted the American public.

They were riveted to the hearings.

And I also think that great countries, especially this country, is quite strong enough to engage in a compromise without losing its standing in the world, without losing its prestige as a great nation.

On the contrary, I think it would be one of the greatest victories for us and our prestige if we could be ingenious enough and magnanimous enough to bring about some kind of a settlement of this particular struggle.

NARRATOR: Fulbright invited the respected diplomat George Kennan to testify.

For two decades, his doctrine of containment-- stopping Soviet expansion-- had been the basis of American foreign policy, and had in some ways been the justification for leading the United States into its proxy war in Vietnam.

KENNAN: The first point I would like to make is that if we were not already involved as we are today in Vietnam, I would know of no reason why we should wish to become so involved, and I could think of several reasons why we should wish not to.

You have referred to containment here.

How... how can we contain in Vietnam?

We would do better if we really would show ourselves a little more relaxed and less terrified of what happens in the... certainly in the smaller countries of Asia and Africa, and not jump around like an elephant frightened by a mouse every time these things occur.

NARRATOR: Johnson was relieved when, at the last moment, instead of airing Kennan's testimony, CBS showed reruns of The Real McCoys, The Andy Griffith Show and I Love Lucy.

But NBC kept the cameras running.

This is not only not our business, but I don't think we can do it successfully.

And I take it by this you mean that this is simply not a practicable objective, as I understand it, in this country.

We can't achieve it even with the best of will.

This is correct, and I have a fear that our thinking about this whole problem is still affected by some sort of illusions about invincibility on our part.

NARRATOR: Just before the hearings began, the president had decided to resume the bombing of targets in North Vietnam.

The 37-day pause that had begun on Christmas Eve 1965 had yielded no hint of Hanoi's willingness to come to the negotiating table.

In South Vietnam, Viet Cong guerrillas were now believed to control nearly three-quarters of the country.

But General William Westmoreland, the American commander, thought his most urgent task was to destroy the North Vietnamese regular army units Hanoi was sending South.

Westmoreland's target for the next two years would be reaching what he called the "crossover point"-- the point at which U.S. and ARVN forces were killing more enemy troops than could be replaced.

It would be a war of attrition.

But that would require still more American soldiers.

They came from every corner of the country.

MATT HARRISON: I was born at West Point when my dad was on the faculty there.

From my earliest recollection, West Point was what I wanted to do, not even particularly because I had an inkling or a strong desire for a military career.

It's just... West Point was kind of the height of my ambition.

("On, Brave Old Army Team" playing) NARRATOR: The son of a colonel who had served in World War II, Matt Harrison had grown up on Army bases around the world.

For him and his four siblings, the military was always at the center of their lives.

ANNE HARRISON BOWMAN: You addressed parents "sir" and "ma'am," and you said "yes" and not "yeah."

And you answered the phone, "Colonel Harrison's quarters."

We got up every Saturday morning and we dusted the house.

My dad would put on the West Point marching band and my sister and I would dust around the living room.

NARRATOR: It seemed to Matt's parents that he could do no wrong.

He was the embodiment of the values they had hoped to instill in all their children: duty, honor, and country.

HARRISON: The strongest impression I have from my class and my classmates was they were guys who just were idealists.

And I think guys drawn from little towns all across the United States had that in common.

It was a time before the questions about American exceptionalism.

We didn't question.

We believed in what this country stood for, and we believed that people who had the ability to lead soldiers should do that.

("Mustang Sally" by Wilson Pickett playing) PICKETT: ♪ Mustang Sally ♪ ♪ Huh!

♪ ROGER HARRIS: I wanted to go with the gladiators.

I wanted to go with the tough guys.

I was born in Boston, in the Roxbury section of Boston.

There were those who would recruit you for gangs and try to entice you to do things that-that weren't in the best interest of society.

Let's put it like that.

NARRATOR: Roger Harris dreamed of going to college on a football scholarship, but was not big enough to play for his team in high school.

HARRIS: And so I enlisted in the Marine Corps.

And I felt that... that it was a win-win because, one, if I died, then my mother would be able to receive the $10,000 insurance policy.

I thought that was a lot of money, that my mother will be rich if I die.

You know, she'll be rich.

If I live, then I'll be a hero, you know, and I can come back and get a job.

Naive, dumb, you know?

NARRATOR: John Musgrave was from the Fairmount neighborhood of Independence, Missouri.

MUSGRAVE: I was 17 and my best friend and I went down and enlisted in the Marine Corps.

I had always dreamed of being a Marine.

And... Well, I knew I wasn't going to be a man right away but I was going to be a Marine, and that was enough.

I'd be doing something mature.

And I'd be doing something that was important.

And there was a war on and I wanted a piece of it.

BILL EHRHART: I grew up in Perkasie, Pennsylvania.

And every Memorial Day all that generation of World War II would dress up in their American Legion uniforms and parade around.

And I'd put red, white, and blue crepe paper on my bicycle.

And the kids could ride behind the parade.

NARRATOR: Bill Ehrhart would sign up in part because his father, a pastor, had not served.

Ehrhart was a gifted student and in his senior year in high school was accepted by four colleges.

Had he attended any one of them, he would have been deferred from the draft.

It all came down to this notion of I was going to serve my country and be a hero and have that gorgeous Marine Corps uniform.

And the girls would just be draped around my neck and nobody would beat me up again.

But at the same time I would really be serving my country.

It was my chance to be... (sighs) one doesn't want to trivialize it, but it was my chance to be the star of my own John Wayne movie.

It was my chance to do what that World War II generation had done and seemed to be so proud of.

Now I had my turn.

NARRATOR: Wherever they came from, whatever their reasons for joining the military, training transformed them.

(United States Marine Band playing "Semper Fidelis" march) For about the first five weeks at Parris Island, I was convinced that I was going to die there.

The drill instructors said they were going to kill me.

And they certainly sounded serious.

MUSGRAVE: I grew up in segregated neighborhoods all my life.

So, I'd never met a black person till I arrived at boot camp.

Never stood next to a black person or a Hispanic or anyone who was Jewish.

I just... they didn't mix where I grew up.

So that was just eye opening.

But when I got to talking to everybody, we were all the same.

We were all working class and poor.

And we all wanted to be Marines real bad.

EHRHART: By the time I graduated, I felt like I was king of the world.

I was God.

I could do anything.

On that day I became a Marine.

You know, the Marine Corps trains you to be a fighter.

They train you to fight, they train you to kill.

They used to say that if you're a Marine, you can't die until you kill three Vietnamese.

And I said, "Well, I'm from Roxbury.

If the expectation is three, I'll do ten."

You know, craziness.

(gunshot) LESLIE GELB: The tendency for a great power is to use what it's greatest at-- namely its firepower, destructive power.

Dropping a lot of bombs and shooting a lot of artillery at a distance.

You save lives.

You kill a lot of them, you don't lose a lot of us.

NARRATOR: The central coastal province of Binh Dinh was home to more than half a million people.

For decades, it had been a guerrilla stronghold, and in early 1966, the Viet Cong had been augmented by North Vietnamese regulars, some 8,000 men in all.

General Westmoreland sent 20,000 American, South Vietnamese and South Korean troops storming across the province in pursuit of the enemy and their sources of supply.

They first dropped leaflets and broadcast from loudspeakers to warn villagers of the terrible fate that awaited anyone who fired on their helicopters, urged them to leave their homes, promised safe passage to any Viet Cong who wished to surrender.

Then they called in airstrikes and artillery and blew the hamlets to bits.

It was the first large-scale search-and-destroy campaign of the war.

(shouting, gunfire) The offensive lasted 42 days.

The Army reported 2,389 enemy soldiers killed.

Westmoreland was pleased.

But commanders on the scene were concerned that despite all the American firepower brought against them, most of the North Vietnamese regulars had still managed to escape back into the Central Highlands.

The operation would drive more than 100,000 civilians from their homes.

Similar search-and-destroy and bombing campaigns-- 17 large-scale U.S. offensives in 1966 alone-- would produce a total of more than three million homeless people all across the country, roughly one-fifth of South Vietnam's population.

Since there was no front in Vietnam, as there had been in the first and second World Wars, since no ground was ever permanently won or lost, the American military command in Vietnam-- MACV-- fell back more and more on a single grisly measure of supposed success: counting corpses.

Body count.

JAMES WILLBANKS: The problem with the war, as it often is, are the metrics.

It is a situation where if you can't count what's important, you make what you can count important.

So, in this particular case what you could count was dead enemy bodies.

JOE GALLOWAY: You don't get details with a body count.

You get numbers.

And the numbers are lies, most of 'em.

If body count is your success mark, then you're pushing otherwise honorable men, warriors, to become liars.

ROBERT GARD: If body count is the measure of success, then there's the tendency to count every body as an enemy soldier.

There's a tendency to want to pile up dead bodies and perhaps to use less discriminate firepower than you otherwise might in order to achieve the result that you're charged with trying to obtain.

(man shouting) MERRILL McPEAK: Just think about the problem from the North's point of view.

They had to supply the South.

I'm talking about bringing in people, equipment, supplies, and so forth.

They started from nothing and pushed a road through that... through an area the size of Massachusetts.

So this is not a trivial amount of real estate that they took over, built a road on, and then maintained it.

NARRATOR: For years, Hanoi had smuggled most of its arms and supplies to the South aboard an improvised fleet of junks, trawlers and freighters.

But when the U.S. Navy effectively blockaded the Southern coastline, the North Vietnamese would be forced to move almost all of their supplies overland, through Laos and Cambodia, neutral countries Hanoi considered part of the greater battlefield.

Americans called it the Ho Chi Minh Trail.

The North Vietnamese called it Route 559, after the men and women of the 559th Army Corps, who were turning it from a braided web of footpaths into 12,000 tangled miles of jungle roadways down which men and materiel streamed south.

When they had fought the French, the Viet Minh had depended on tens of thousands of porters, then on legions of bicycles.

Now, to offset the growing American presence, the North Vietnamese used more mechanized transport-- relays of six-wheeled Russian-built trucks traveling under cover of darkness.

MACV reasoned that if the Ho Chi Minh Trail could somehow be sufficiently damaged, the enemy would be unable to sustain itself.

Three million tons of explosives would eventually be dropped on the Laos portion of the trail alone-- a million more tons than fell on Germany and Japan during all of World War II.

Some key choke-points were hit so many times the workers gave them names-- "the Gate of Death," "Fried Flesh Hill" and "the Gorge of Lost Souls."

To expose enemy traffic, other aircraft dropped chemical defoliants, including Agent Orange, that destroyed thousands of acres of jungle and turned the earth into what one American pilot called "bony, lunar dust."

McPEAK: We'd punch a hole in the road and say, "Ha ha, they'll never get around that one."

And the next day you'd come up, and the hole wouldn't be there; and there'd be dust on the trees back, you know, 50 meters in both directions, saying, heavy traffic all night.

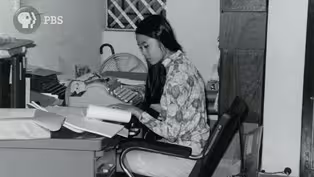

DONG SI NGUYEN: NARRATOR: As many as 230,000 teenagers, many of them volunteers, worked to keep the roads open and the traffic moving.

More than half of them were women.

Le Minh Khue, who had left her home in the North with a novel by Ernest Hemingway in her backpack, observed her 17th birthday on the trail.

LE MINH KHUE: NARRATOR: Thousands died on the trail from starvation and accidents, fevers and snakebite and sheer exhaustion, as well as from the relentless bombing.

LE MINH KHUE: TRAN CONG THANG: (Doug Wamble's "A Hard Rain's A-Gonna Fall" playing) HOWARD K. SMITH (on TV): But in this kind of war you never know.

You have to be constantly alert because you can't tell friends from enemies.

Relax for a moment and your reward may be a grenade or a hail of bullets.

CAROL CROCKER: I couldn't watch the news.

My parents would be sitting in front of the television and I would hide in the kitchen.

Of course you don't tell anybody, but it was too much.

I really didn't want to know.

("Smokestack Lightnin'" by Howlin' Wolf playing) HOWLIN' WOLF: ♪ Oh-oh, smokestack lightnin'.

♪ NARRATOR: Mogie Crocker had spent most of his boyhood reading about war.

But nothing had prepared him for what he would experience in Quang Duc Province on the Cambodian border.

He had deliberately fouled up his work at battalion headquarters so badly that he had finally been reassigned to what he wanted most-- a combat unit.

HOWLIN' WOLF: ♪ Whoa-oh, tell me, baby ♪ ♪ What's the matter with you?

♪ ♪ Why don't you hear me cryin' ?

♪ Oooh ♪ JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: Not hearing in those days was so difficult.

There'd be at least eight to ten days usually between letters.

So knowing he was in action, you just didn't know what, you know, might be going on.

NARRATOR: Mogie's battalion commander, Lieutenant Colonel Henry Emerson, known as "The Gunfighter," was courageous, implacable, relentless.

A few months before Mogie got there, he had offered a case of whiskey to the first of his men to bring him the hacked-off head of an enemy soldier.

They did.

For nine days in early May of 1966, Mogie and his outfit battled nothing but the terrain.

They struggled through a labyrinth of elephant grass and thorn bushes, bamboo taller than three men and triple-canopied jungle so thick it sometimes took an hour to move 100 feet.

(thunder rumbles) The monsoon had begun.

Sunlight rarely reached the forest floor.

Finger-long black leeches caused wounds that quickly became infected.

When Colonel Emerson learned that four companies of North Vietnamese were preparing an ambush, he decided to ambush the ambushers.

On May 11, he ordered his men to attack, backed by massive air and artillery strikes.

Before the fighting ended, some 2,000 shells had slammed into the enemy positions.

Blood was everywhere, pooled on the ground, smeared on leaves and grass and bamboo.

There were scores of corpses, torn to pieces or blown into the earth, hidden in thickets, half-buried in scooped-out graves.

The earth-shaking concussions had blown the eyeballs of some of them from their heads.

In the midst of the fighting, Mogie's squad was moving along a narrow path when two enemy machine guns opened up on them.

(gunfire) His closest friend was fatally wounded.

Mogie crouched in front of him, radioed for suppressive fire, and then, as both machine guns continued shooting, he carried his dying friend off the battlefield.

For his courage, he would be awarded the Army Commendation Medal.

In his letters home, Mogie told his family nothing of what he'd seen or done.

(David Cieri playing "Sound of Silence") JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: One day when I was at the post office mailing something, I asked the clerk, "How do they let you know if your son is wounded?"

It was very hard for me to form those words.

But I just felt I've got to know.

I just felt so suspended in space, in anxiety.

And the man said, "Now, don't ask that.

Don't think about that."

I said, "Well, I have to know."

And he said, "Don't worry, they'll tell you."

(Pete Seeger playing "The Willing Conscript") SEEGER: ♪ Oh sergeant, I'm a draftee ♪ ♪ And I've just arrived in camp ♪ ♪ I've come to wear the uniform and join the martial tramp ♪ ♪ And I want to do my duty, but one thing I do implore ♪ ♪ You must give me lessons, sergeant ♪ ♪ For I've never killed before.

♪ PHILIP CAPUTO: I didn't like the war protesters whatever.

I kind of felt that they were privileged, spoiled kids who may have been protesting because they didn't want to go.

So they leave it to some guy that maybe got through two years of high school to go do it for 'em.

BILL ZIMMERMAN: The war by 1966 began to impact the middle class because the draft calls had to be enlarged.

They couldn't get enough people to volunteer or draft people out of the working class.

They started drafting people out of college.

And that's when the antiwar movement shifted from a moral movement to a self-interest movement driven by people who didn't want to go to war and their loved ones who didn't want them to go to war.

SEEGER: ♪ And I know that it won't matter ♪ ♪ That I've never killed before.

♪ (school bell rings) NARRATOR: Bill Zimmerman was a graduate student at the University of Chicago in May of 1966.

The son of Eastern European refugees, he'd worked for civil rights in Mississippi and had been opposed to American involvement in Vietnam since 1963.

The draft was a consuming issue for young men of Zimmerman's generation.

Since 1942, every male citizen of the United States had been required to register at age 18.

But of the nearly 27 million American men who came of age during the Vietnam War, more than half avoided military service through exemptions and deferments.

Nearly 500,000 Americans applied for conscientious objector status on religious or moral grounds, six times as many as in World War II.

In all, 170,000 were allowed to perform alternative service in hospitals, homeless shelters, and schools.

Some were trained as medics and sent to Vietnam.

At least two were killed; both received the Congressional Medal of Honor.

A million young men served in the Reserves or National Guard with the expectation they would never be sent into combat.

Reservists and Guardsmen were almost always white, generally better educated, better connected, and better paid than draftees.

Interrupting their lives, President Johnson felt, would have increased opposition to the war.

"If you've got the dough," GIs said, "you don't have to go."

("Backlash Blues" by Nina Simone playing) The result was an Army heavily skewed toward minorities and the underprivileged.

SIMONE: ♪ Mr.

Backlash, Mr.

Backlash ♪ ♪ Just who do you think I am?

♪ ♪ You raise my taxes, freeze my wages ♪ ♪ And send my son to Vietnam.

♪ NARRATOR: For a time, African Americans, though they represented only 12% of the population, suffered a disproportionate number of casualties.

Resentment began to grow.

STOKELY CARMICHAEL: We've got to build so much strength in building our community, that if they come to get one person, they going to have to mess with us all.

That's what we got to do!

That's what we go to do.

(applause) We've got to build so much strength inside our community, so that when LBJ says, "Come here, boy, to my war," we say, "Hell no, we ain't going."

(applause) SIMONE: ♪ But the world is big.

♪ MUHAMMAD ALI: I'm not going to help nobody get something my Negroes don't have.

If I'm going to die, I'll die now, right here fighting you, if I'm going to die.

You my enemy, my enemy is the white people, not Viet Congs, or Chinese, or Japanese.

You my opposer when I want freedom.

You my opposer when I want justice.

You my opposer when I want equality.

And you want me to go somewhere and fight, but you won't even stand up for me here at home.

NARRATOR: At first, 10,000 draftees were called up each month, but in 1966, the growing demand for fresh troops in Vietnam raised that number to 30,000.

Now, thousands of college students could no longer expect a deferment.

ZIMMERMAN: And if your rank fell below a certain threshold, you were yanked out of college.

And the worst that could happen to you is you would be killed in Vietnam.

So we protested at the University of Chicago that the university was complicit with this war by agreeing to supply those rankings to the draft board.

We thought for the first time, you know, we're really having an impact.

NARRATOR: But a majority of Americans, old and young, supported the war.

The Young Americans for Freedom, created by the conservative writer William F. Buckley, held counter-demonstrations on campuses across the country.

CROWD: ♪ His truth is marching on.

♪ LE QUAN CONG: DUONG VAN MAI ELLIOTT: I was brought up to believe that the communists were people who destroy the family, destroy religion, and people who had no allegiance to our country but to international communism.

My mother would describe them as (speaking Vietnamese), which means that these are people with the head of a water buffalo and the face of a horse, meaning that they were subhumans, and they were brutal.

But on the other hand I thought they also include people like my sister Thang and a lot of my cousins.

I couldn't quite reconcile the two images.

But of the two, I think the other image was much stronger because I was so scared of them.

I thought these people must be really, really horrible people.

That was the frame of mind I had when I started doing research into the communist movement.

NARRATOR: Duong Van Mai was the daughter of an official in the South Vietnamese government and was now married to an American, David Elliott.

Back in 1964, she had gone to work for the RAND Corporation in Saigon.

The think tank had been commissioned by Robert McNamara to do a study of enemy prisoners to find out "Who are the Viet Cong?

And what makes them tick?"

DUONG VAN MAI ELLIOTT: I remember my first interview.

I was by myself.

I was very young and I was going to this pretty grim prison to interview this high-ranking cadre who had been captured.

I went in thinking I'm going to meet this beast, you know, this guy with the head of a water buffalo and the face of a horse.

He walked in and he was very surprised to see me.

(chuckles) Just as surprised as I was to see him.

Here was a man who had devoted all his life to fight for what he called a just cause to free his country of foreign domination, to reunify the country under just government.

So he really totally believed in it to the point that he sacrificed his whole life to this cause.

So I left, I was very...

I was very impressed with him.

NARRATOR: When the RAND report was presented to McNamara's top deputies at the Pentagon, describing the Viet Cong as a dedicated enemy that "could only be defeated at enormous cost," one senior official said, "If what you say is true, "we're fighting on the wrong side, the side that's going to lose this war."

(Donovan's "Sunshine Superman" playing) DONOVAN: ♪ Sunshine came softly through my a-window today ♪ ♪ Could've tripped out easy a-but I've a-changed my ways.

♪ STUART HERRINGTON: The overall myth of an American army running roughshod by policy, by strategy, by tactics to terrorize and murder and victimize the innocent population of South Vietnam, that image is the... it-it doesn't do justice to the young men and women who served over there.

It's certainly not an accurate depiction of what our army was about.

NARRATOR: From the first, the Johnson administration understood that the war could not be won without convincing poor farmers living in the countryside that the government in Saigon, not the Viet Cong, had their best interests at heart.

In addition to the military, many American aid organizations were at work in Vietnamese villages.

They dug wells and built windmills, started schools, introduced improved rice, provided medical care, and electrified much of the countryside.

Under pressure from Robert McNamara, MACV struggled to find ways to measure the progress of pacification in South Vietnam's 44 provinces, 220 districts and 13,000 hamlets, and finally came up with the Hamlet Evaluation System.

Soon some 220 U.S. district advisers were required to produce some 90,000 pages of data every month-- a mountain of information so daunting no one could make sense of it.

PHILIP BRADY: Everything can be quantified.

So you can literally say, "How pacified is this village?"

"It's 37.5% pacified."

Well, what does that mean?

An American would tell you, "You know, we haven't had an incident in this village or this province," whatever.

"The incident rate's going down, and therefore we're winning."

But we would point out that certain troubled areas in the provinces that we were working in, we would say simply that it's not pacified unless you want to consider it pacified by the other side.

HERRINGTON: To the extent that pacification was succeeding, schools were being built, wells were being cleaned.

And then one fine night here comes 400 North Vietnamese soldiers into the village, executes the village chief, kidnaps 12 of the young people for, you know, service in the revolutionary armed forces, and the people look at the government and say, "You promised us you'd protect us, but you didn't stay."

MIKE HEANEY: I was over there early.

I was with a really good unit, who believed in Army traditions, they believed in honor, they believed even in treating your enemy humanely once he was a POW.

NARRATOR: Lieutenant Mike Heaney from Basking Ridge, New Jersey, was a platoon leader in the 1st Cavalry Division.

He'd arrived late in 1965 and was assigned to a densely populated section of central Vietnam, where he found himself surrounded by North Vietnamese infiltrators and villagers whose loyalties were unclear.

HEANEY: We never really figured out how to determine who the enemy was.

Being normal, decent American boys, you don't just put your rifle up and take a shot at a guy and try to kill him unless you're pretty sure this is an enemy.

And if he wasn't armed, or wasn't menacing you in any way, we wouldn't shoot him.

We'd go through a village in which there would be no people we could identify as enemy soldiers, and we'd find a big cache of rice.

So the standing instructions were blow that up, burn it, destroy it, poison it, whatever.

We really didn't want to do that because it... You didn't have to be a rocket scientist to look around and see these people are depending on this.

This is their food.

We were told sometimes to burn thatched dwellings.

And guys would unenthusiastically try to light a roof.

And as soon as the flame burned out, they weren't going to try again.

Our hearts really weren't in trying to destroy civilian food, civilian homes.

It gave us an uneasy feeling about, "What is this war is about?"

(gunfire) NARRATOR: Most of the fighting in Vietnam was the kind Mike Heaney was about to see-- small-scale, close-up, and initiated by the elusive enemy.

The military called it "contact."

"War is hell," grunts liked to say, "but contact is a mother."

HEANEY: The job of an infantry platoon usually is to try to scare up enemy infantry and take it down.

Really, the tactic was we were acting as bait.

And at some level we knew that.

You know, go walk in the woods and draw fire.

NARRATOR: Six months into his tour, Heaney undertook what he and his men thought would be an easy assignment: climb a slope not far from their base at An Khe and drive a small enemy mortar unit off a ridge line.

HEANEY: As soon as we started out, we started to get some bad vibes.

We found some boot prints in the mud at the edge of this landing zone, and a nice trail, a well-used trail going up the ridge.

I remember talking to one of my squad leaders about this.

And we were both sitting there, "Well, ..., this sucks."

And all of a sudden the very point man, the first guy in the column, Sergeant Mays, without saying anything just put his M16 up to his shoulder and fired off a round.

And he turned around and he said, "VC on the trail.

VC on the trail."

Before I had a chance to digest this, he went down, shot right through the chest.

(bullet hitting) Boom!

And all of a sudden what was a very well-laid ambush erupted.

And it was so loud and so unexpected I was stunned for... for a little bit, you know.

"What the ... is going on?"

NARRATOR: Heaney's radio operator, Private Terry Carpenter, got the company commander on the line.

"We've run into something bad," Heaney said.

At that moment, a bullet hit Carpenter in the head.

HEANEY: I knew Terry was down.

I knew Sergeant Mays was down.

I had asked the first machine gun crew to come up and start laying down machine gun fire.

They got blown away pretty quickly.

They never really had a chance to lay down much fire.

At that point there wasn't anybody left in my forward unit.

Every one of them had been taken down except me.

Every one.

(voice breaking): Every one had been killed or mortally wounded at that point.

NARRATOR: Night fell.

What was left of Heaney's company braced for the assault they assumed would come at dawn.

I was lying there on the perimeter.

I was right next to a dead enemy soldier.

It was kind of my face and his feet and I kept looking back at him, because I couldn't see any wounds on him.

And, you know, the strange things you think, "This guy's going to kill me.

"He's faking it.

"He's waiting until the assault, then he's going to jump up and kill me."

And I almost shot him again.

Just to make sure he was dead.

NARRATOR: Then the enemy began to lob mortar shells among Heaney's men.

HEANEY: I felt like somebody had taken a bat and hit me on my calf, my right calf, as hard as he could.

I was so stunned by the shock of being hit, and I just drew in a deep breath of air in terrible pain.

I couldn't speak.

Right after the ambush happened, and I knew I'd lost a bunch of guys, I said a prayer to God saying, basically, "If you need any more guys from my platoon, take me.

Don't take any more of my men."

As soon as I said it, I freaked myself out and said, "Holy ..., can I take that prayer back?"

But it was too late.

I'd-I'd said it.

And as it turns out, not one more man in my platoon died after that prayer.

NARRATOR: American artillery finally zeroed in on the enemy.

The survivors of Heaney's company stumbled down the hill to safety.

He was carried to a hospital.

HEANEY: I was lying on my bed sobbing.

And this nurse came over.

She bent over and said, "Lieutenant... "You... the-the your men are all over the place.

You've gotta stop crying."

And at that point my platoon sergeant, huge black guy from Detroit whom I loved dearly, Sergeant Sam Hunt, he came over and he sat down next to me (voice breaking): and he took my hand and he said to this nurse, "Ma'am, this here lieutenant don't have to stop doing anything."

LE CONG HUAN: (crowd shouting angrily) JOHN LAURENCE: The students are angry now.

And the word is passed to gather at Saigon's main Buddhist pagoda after dark.

JOHN QUINN: After all these years, the Vietnamese have learned to live with crises and war.

But they haven't learned yet to live as a nation.

JOHNSON: Now, Dean, what are we gonna do?

Are we moving to the point where it would be difficult for us to ask people to continue to die out there, this kind of stuff going on every two or three months?

DEAN RUSK: I think not yet, sir, by any means.

I think that this is still a minority problem.

But political talk is not gonna be able to get anywhere if they don't maintain the elements of order.

NARRATOR: On May 15, 1966, the government of South Vietnam, the country for which so many Americans were risking their lives, again seemed on the brink of collapse.

The ascendancy of Prime Minister Ky had dealt a severe blow to activist Buddhists, who had been demanding representative government and a negotiated end to the war since 1963.

When Ky suddenly fired a rival general, a popular Buddhist commander, demonstrators poured into the streets of Hue and Danang.

They shut down the port through which U.S. supplies had been flowing.

Some South Vietnamese soldiers, loyal to the dismissed general, abandoned the struggle against the communists and headed for the city.

Angry crowds burned American jeeps.

Signs reading "Peace!"

and "Americans Go Home!"

appeared everywhere.

President Johnson was so concerned, he asked his advisors to ready a fallback position if the Ky government fell.

If necessary, he said, the U.S. should be prepared to get out of Vietnam and perhaps make a stand against communism in Thailand instead.

Ky ordered South Vietnamese soldiers to surround and subdue Danang, where they exchanged fire with their former comrades.

As Ky's forces stormed Buddhist pagodas in Danang, his warplanes strafed dissident troops occupying the central market.

The rebellion was crushed.

Washington was relieved.

Ky seemed to be back in control.

But from his command post on a hilltop outside the city, an American Marine lieutenant had watched in disbelief as two battles unfolded simultaneously: in the west, his fellow Marines were fighting the Viet Cong; in the east, the South Vietnamese army seemed to be at war with itself.

(Simon and Garfunkel's "The Sound of Silence" playing) ♪ Hello darkness, my old friend.

♪ MOGIE CROCKER (dramatized): May 16, 1966.

Dear Mom and Dad-- Our operation here on the Cambodian border has been quite a success.

No doubt you will hear about it on the news.

We keep getting more and more operations thrown at us so that nothing is very sure.

SIMON AND GARFUNKEL: ♪ ...that was planted in my brain still remains.

♪ CROCKER: Whether I will go out again soon I don't know, but don't plan on steady mail.

Tell Randy I'm looking forward to seeing his new dog.

I may take a 15-day leave to Tokyo to keep from cracking up.

SIMON AND GARFUNKEL: ♪ 'Neath the halo of a street lamp.

♪ JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: It was a lovely spring day, and I opened the letter that said that.

And I was just really devastated because by that time Vietnam was in total chaos.

There was a continuing changeover of people in authority at the government in South Vietnam.

And there were protests of the Buddhist monks and others that... there were anti-American demonstrations.

I just thought, "Why?

Why are we there?"

CAROL CROCKER: I think that letter when my brother showed a kind of despair is probably the first time he'd expressed that openly to the whole family.

It echoed back to the day he'd said to me, "I don't want to go back."

NARRATOR: To an old high school friend, Mogie was even more forthcoming.

MOGIE CROCKER (dramatized): Dear Duff, Since I last wrote, which is several months, a number of exciting but terribly unpleasant events have occurred, the worst of which was being pinned down by two Chinese light machine guns firing 900 rounds per minute and having my best friend killed more or less beside me.

Someday I may tell you the whole story if my nerves aren't completely gone by then.

Actually the latter is just wishful thinking, in false hope they will take me off the line.

I was fantastically religious for a while, sending up various and sundry prayers mainly concerned with trying to stay alive, but I am once again an atheist until the shooting starts.

(gunfire) (drums playing up-tempo march cadence) HARRISON: I really believed that we had to stop the communist expansion.

I also believed that we were on the side of the angels.

Just as France had provided us with support during our revolution, we were providing the South Vietnamese with support during their revolution.

NARRATOR: Matthew Harrison was among the 300 graduates of the class of 1966 who volunteered to go to Vietnam.

MAN: Rangers!

MEN: Rangers!

MAN: All the way!

MEN: All the way!

NARRATOR: But first, he went to Florida to become a Ranger and endured nine weeks of the most demanding training the Army had to offer.

MAN: Airborne daddy gonna take a little trip!

MEN: Airborne daddy gonna take a little trip!

NARRATOR: The man in charge was Major Charles A. Beckwith-- Chargin' Charlie-- hero of the siege of Plei Me the year before.

"If a man is bloody stupid," he told each group of newcomers, "his mother will receive a telegram and it will say, "'Your son is dead because he's stupid.'

"Let's hope your telegram only reads, 'Your son is dead.'

"With the training we're going to give you here, "maybe your mother won't receive any telegram at all.

So pay attention."

To make it through, Harrison and his fellow trainees had to survive days without sleep; were deprived of food and water, forced to march up mountains until their feet bled and patrol through swamps that harbored copperheads and cottonmouths; had to learn how to detect booby traps and outmaneuver veterans masquerading as Viet Cong.

"Expect the unexpected," Beckwith told his trainees again and again.

"Life is unfair."

Once he'd become a Ranger, Harrison was eager to get to Vietnam and put into action the survival and leadership skills he'd been absorbing for five years.

HARRISON: I remember discussing with my classmates how horrible it would be to serve in the Army if everybody just a year ahead of us had served in combat and we didn't have the opportunity to do that.

I was afraid we were going to win the war too quickly and I wouldn't have a chance to experience it.

("L'Assassinat De Carala" by Miles Davis playing) NARRATOR: June 3, 1966, was Mogie Crocker's 19th birthday.

His company was involved in yet another campaign, aimed at finding and killing North Vietnamese troops filtering into the Central Highlands from Laos.

As night fell, Mogie and his squad were ordered to move up toward the crest of a hill overlooking a besieged ARVN outpost so that artillery could be brought up and positioned to shell the enemy in the morning.

They moved slowly, warily up the slope.

Mogie was the point man.

Out of the darkness, a machine gun opened up.

(gunfire) Denton Crocker, Jr. never made it to the top of the hill.

("One Too Many Mornings" by Bob Dylan playing) DYLAN: ♪ Down the street the dogs are barkin' ♪ ♪ And the day is a-gettin' dark.

♪ JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: It was just a lovely day to be out in our garden.

Candy, our little girl, went to a birthday party.

And the other children were just around the house, I guess.

But shortly after lunchtime, I stepped out on the porch.

I saw two men in uniform coming to the house.

And I knew something terrible had happened.

And I ran down the steps.

And I just grabbed hold of one of them and said, "Don't tell me.

Don't say it.

Not my beautiful boy."

And he just said, "Yes."

DYLAN: ♪ From the crossroads of my doorstep ♪ ♪ My eyes start to fade.

♪ CAROL CROCKER: I was sitting on the couch in the living room.

I suddenly heard my mother screaming for my father.

Like in a movie, here came the priest up the stairs with a soldier, and she's going, "Oh no."

And she's calling my dad.

My reaction was to leap up off the couch, race out the back door and I grabbed my little brother's hand and I just started walking.

I said, "You have to come with me."

I said, "I have something to show you."

I have no idea where I was going.

I just said to myself, "No.

This isn't going to happen."

And something made me turn around and I walked up to the back of the house from the alley.

And my dad was standing there.

And I fell into his arms and I said, "Don't let it be true, Dad.

Is it true?"

And he said, "Yes."

I somehow knew that things had changed forever.

That my mom as my mom and my dad as my dad, it was never going to be quite the same again.

I just, I remember sitting on the couch and I put my arms around them and I said, "We'll love each other and we'll be all right."

But I don't know how far it carried.

You know?

We all tried.

DYLAN: ♪ We're both just one too many mornings ♪ ♪ And a thousand miles behind.

♪ JEAN-MARIE CROCKER: Carol said to me one day very shortly after Denton was killed, probably that very day, "How can you believe in God?"

And I said, "Because we had Mogie."

And I think that his life was a real gift.

It was a privilege to have him.

A friend wrote to me, "Our children are really only on loan to us," which I guess is true.

NARRATOR: Ten days later, an Army captain escorted Mogie's body to Dick Stone's funeral home.

The family priest had suggested that Mogie be buried in Saratoga Springs so that his parents could easily visit his grave.

But they chose Arlington National Cemetery instead.

"A corner of my heart knew," his mother remembered, "that if he were buried near us, I would want to claw the ground to retrieve the warmth of him."

(applause) LYNDON JOHNSON: I hear my friends say, "I am troubled," and "I am confused," and "I am frustrated," and all of us can understand those people.

Sometimes I almost develop a stomach ulcer myself, just listening to them.

And we all wish the war would end.

We all wish the troops would come home.

There is no human being in all this world who wishes these things to happen, for peace to come to the world, more than your president of the United States.

("The Beginning of the End" by Nine Inch Nails playing) NARRATOR: The military claimed to have killed some 57,000 enemy soldiers in the first six months of 1966.

But privately the administration worried that General Westmoreland's "crossover point"-- the moment when more enemy soldiers had been killed than could be replaced-- seemed no nearer.

From the first, the Joint Chiefs had urged the president to be more aggressive-- to permit troops to pursue the enemy into Laos and Cambodia and to expand the target list for bombing in North Vietnam.

Johnson still would not allow borders to be crossed by regular ground troops for fear of bringing China or even the Soviet Union into the war.

And he was wary of heavier bombing, fearful of hitting more civilians.

But despite his concern, the president now agreed to intensify the bombing campaign called Operation Rolling Thunder.

He approved attacks on oil facilities all over North Vietnam, including some sites adjacent to the cities of Haiphong and Hanoi.

His commanders assured him that this would be a mortal blow to the enemy, sure to force the North Vietnamese to the bargaining table.

Tens of thousands of sorties were flown.

Many bombs hit their intended targets.

But many missed and fell on residential neighborhoods instead, just as the president had feared.

JOHNSON: Things are going reasonably well in the South, aren't they?

McNAMARA: Yes, I think so.

Because we think we're taking a heavy toll of them, but it just scares me to see what we're doing there with God knows how many airplanes and helicopters and firepower and going after a bunch of half-starved beggars.

This is what's going on in the South.

And the great danger is that, that they can keep that up almost indefinitely.

The only thing that'll prevent it, Mr. President, is their morale breaking.

There's no question but what the troops in the South, the VC and North Vietnamese, they know that we're bombing in the North.

And we just have a free rein.

And when they see they're getting killed in such high rates in the South, and they see that the supplies are less likely to come down from the North, I think it will just hurt their morale a little bit more.

And to me that's the only way to win because we're not killing enough of them to make it impossible for the North to continue to fight.

But we are killing enough to destroy the morale of those people down there if they think this is going to have to go on forever.

JOHNSON: All right.

Go ahead, Bob.

BAO NINH: HO HUU LAN: McPEAK: People talk about collateral damage, but it means something.

You don't want to do collateral damage.

You want to do the damage you want to do.

That's the winning way to do this.

(distant, echoing shouting) EVERETT ALVAREZ: Even though I was in a cell by myself and others were in by themselves, we weren't alone.

We were together in this old French prison halfway around the world from the United States.

Gradually I began to realize this could go on a long time.

A long time to me was like maybe a year or two.

I never dreamed it would be eight-and-a-half years.

NARRATOR: By the summer of 1966, Lieutenant Everett Alvarez, the first American pilot to have been shot down over North Vietnam, had been a captive for nearly two years and had been joined in and around Hanoi by more than 100 other downed airmen.

Even though the North Vietnamese considered them all "aggressors," "criminals," and "air pirates" rather than prisoners of war deserving of humane treatment, Alvarez and the others had been treated relatively well at first.

But that hadn't lasted long.

The men were soon forbidden to communicate with one another, forced to bow to their jailers, and told that their country had forgotten them.

They were subjected to isolation, beatings, and hour upon hour of torture, all aimed at forcing them to admit their guilt and record statements denouncing the war.

(door slams) ALVAREZ: When that cell door would open, when they would say, "You, your turn," you know, the bottom just fell out of you, and you knew that you may not come back.

The manacles, the ropes, the beatings, they broke bones.

They... they did everything.

My arms turned black from the cuffs that cut off all circulation.

And they didn't let me die.

They just kept the pain.

That's when I realized that I was not a superhuman.

The first time I broke and gave them something, I felt so low.

I felt so little.

NARRATOR: Some of the men who were forced to record statements did their best to make their true feelings known back home.

Commander Jeremiah Denton blinked his eyes to spell out "torture" in Morse code.

On July 6, just one week after American bombs had first fallen on Hanoi and Haiphong, jailers rounded up Alvarez and 51 other prisoners, and, while cameras rolled, marched them through downtown Hanoi, past the angry citizens of the city.

ALVAREZ: I could hear the crowd being whipped up.

And as I passed this one fellow with the megaphone, he looked at me and he yelled to the crowd.

"Alvarez, Alvarez, son of a bitch, son of a bitch!"

People started pressing in, throwing things-- bottles, shoes.

But the guards by this time were having a hard time keeping the people away.

NARRATOR: The North Vietnamese had hoped to rally international support for trying the prisoners as war criminals.

It backfired.

People everywhere, even many of those who opposed the war, sympathized with the stumbling, helpless men.

Plans for public trials were canceled.

The bombing continued, and more American planes were shot down.

The North Vietnamese took pride in capturing American airmen.

Even children were expected to do their part.

(call and response with teacher and children) TEACHER: Hands up!

Hand up!

TEACHER: Hands up!

Hands up!

TEACHER: Hands up!

McPEAK: The bombing around Hanoi and Haiphong that resulted in so many of our people being POWs for a long period of time was fought out of the White House basement, with the president himself picking targets, and deciding that we're going to attack now, and then we're going to pause for awhile.

Airpower was being misused, big time.

NARRATOR: Operation Rolling Thunder did destroy most of North Vietnam's oil storage facilities.

But the North Vietnamese shifted most of their oil to underground tanks, and more arrived every day from China and the Soviet Union.

The bombing was stepped up anyway.

Throughout the North, enough crude air shelters were fashioned from concrete pipe buried five feet beneath the ground to accommodate some 18 million people-- virtually the entire population.

(workers singing in Vietnamese) Over a million people were said to be working around the clock to undo what American bombs had done.

When key bridges were destroyed, they fashioned pontoon bridges overnight to keep traffic moving.

Crews waited along the roads with heaps of gravel and stone and stacks of wood to fill bomb craters.

They worked under the slogan "The enemy destroys, we repair.

The enemy destroys, we repair again."

(workers continue singing) WILLBANKS: Rolling Thunder was the dumbest campaign ever devised by a human being.

The normal human thing to do is to think that your enemy thinks like you.

There's the old story, apocryphal, that when McNamara wants to know what Ho Chi Minh is thinking, he interviews himself.

What the problem then becomes is that you keep trying to send messages that are rational based upon your judgment of rationality, but have nothing to do with the definition of rationality on the other side.

So what's irrational to us is totally rational to the other side if you've decided that you are going to reunify the Vietnams no matter what it takes, no matter how many casualties.

NARRATOR: Hanoi did all it could to publicize the damage American bombs were doing to civilians.

Most Americans dismissed the reports as communist propaganda.

But when Harrison Salisbury of the New York Times traveled to North Vietnam and reported on Christmas Day, 1966, what he had seen, public doubts about the morality of the war grew.

GELB: A lot of the military we talked to shared our concerns about how the war was being fought, and whether or not it could be won.

But when it came to an official position, it was what we know well, namely, "We can win this war and we're doing it right.

We just need more-- more troops, more bombing."

WILSON: I recall on one instance after I had returned from Vietnam, I went by to see McNamara.

He was saying, "Well, how is our strategic bombing program affecting the course of the war?"

I said, "It is not gaining us anything.

Indeed, it is counterproductive."

He said, "What do you mean?"

"Mr. Secretary, the sledgehammer approach is not working.

"These people know that at some point "we're going to get tired of killing them.

And they think they can outlast us."

And he said, "Why don't people tell me these things?"

I said, "Mr. Secretary, you don't ask."

("I Am a Rock" by Simon and Garfunkel playing) CRAIG McNAMARA: I think every father and son struggles in the course of their lives together.

SIMON AND GARFUNKEL: ♪ In a deep and dark December ♪ CRAIG McNAMARA: And I don't think my dad and I were exempt from that.

The interesting thing for me is the space to talk about Vietnam was never created.

And that was clearly a decision on my father's part.

SIMON AND GARFUNKEL: ♪ I am a rock... ♪ NARRATOR: Craig McNamara, the son of the Secretary of Defense, was a student at St. Paul's School in Concord, New Hampshire, where a teach-in about the war was to be held.

I remember calling my father from a phone booth and saying, "Dad, we're going to have this experience "and if there's any support materials that you think I should present, please let me know."

The support materials didn't come.

I think my father really wanted lovingly to protect me from the Vietnam experience to the best of his ability.

Well, we know you can't do that.

Things bleed through and it just doesn't happen that way.

Probably, he realized at that time that the support materials... weren't there.

ROBERT McNAMARA: Today I can tell you that military progress in the past 12 months has exceeded our expectations.

The Viet Cong have been unable to mount the offensive that they had planned designed to cut the country in half at its narrow waist.

The military pressure, which forces have brought against them, have prevented them from mounting that offensive and have inflicted very heavy casualties on them.

No matter how you measure it, we're better off than we thought we would be at this time.

("Ain't Too Proud To Beg" by the Temptations playing) ♪ I know you want to leave me... ♪ EHRHART: Certainly when I arrived, I'm thinking I'm involved in a winning enterprise.

I mean, America doesn't lose.

We never lose.

I had sort of not really known much about the War of 1812, which was... pretty much of a draw, or the Civil War in which half of America lost, and the Korean War where we won the first half and lost the second half.

But I'd been taught America never loses.

NARRATOR: The Marines had been the first American combat troops to fight in Vietnam.

And they were expected to fight longer than their Army counterparts-- 13 months instead of 12.

Marine privates Bill Ehrhart, John Musgrave, and Roger Harris all arrived at Danang in early 1967.

MUSGRAVE: The first thing that assaulted my nose was the foreign smells.

And watching people relieve themselves by the side of the road and seeing animals I'd never seen before-- the big water buffaloes.

You know, it was like being on Mars, because it was totally foreign to me.

But I honestly, in my dumb Missouri kid kind of way, I thought, "Look at all those foreigners."

And it didn't dawn on me for a little while that the only foreigner in that area was me.

HARRIS: The feeling was that we were going over to rescue folks.

And that the communists were taking over this country and they needed help.

But then when we got there we realized that... that it wasn't exactly like that, you know.

Many of the Vietnamese, they would spit at our trucks and they'd tell us to go back to America.

And then, you know, we began questioning ourselves, you know, why are we here?

These people don't want us here.

NARRATOR: Roger Harris was assigned to G Company, 2nd Battalion, 9th Regiment of the 3rd Marine Division at Phu Bai, outside of Hue.

John Musgrave was first stationed with the 1st Marine Division at the Danang Airbase.

And Bill Ehrhart joined the 1st Regiment of the 1st Marine Division near the city of Hoi An.

Private Ehrhart was given a desk job, collating snippets of information for the daily intelligence summary.

Three days after he got to Hoi An, a group of civilian detainees was brought into the compound.

EHRHART: These two amtracs come in the back gate.

The Marines up top start pushing them off.

Their hands are tied, their feet are tied, they have no way to break their fall.

You literally can hear bones snapping, shoulders dislocate.

And I grab Corporal Sal, and he says in the absolute flattest, hollowest voice I've ever heard, "Ehrhart, you better keep your mouth shut and your eyes open "till you understand what's going on around here.

"Those trackers, they're hitting mines out there "on the sand flats every day.

"They're getting killed; they're getting maimed.

"And these people know where those mines are.

"You treat these people nice in front of the trackers "and those trackers "will rearrange your head and ass for you and walk away laughing."

Well, at that point, three days into Vietnam, I'm thinking, "Whoa.

What the hell is going on here?"

I think it is destroying the good name and the leadership of the United States.

Furthermore, I believe that the war is militarily unwinnable.

I believe that thousands of American young men are being asked to die to save Lyndon Johnson's face.

He must know by now that this war is unwinnable, but he does not know how to give up.

Therefore, I believe that young men are not only justified but to be thanked if they point this out by refusing to take part in such an outrageous war any longer.

("Footprints" by Wayne Shorter playing) NARRATOR: Dr. Benjamin Spock was the best-loved pediatrician of his time; millions of American parents had consulted his bestseller, Baby and Child Care.

In early 1967, he wrote the preface to an article in the leftist magazine Ramparts on the impact of American napalm on South Vietnamese children.

Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. was among those who had read it.

He had been agonizing about the war for months.

But he had been reluctant to break openly with Lyndon Johnson, who had done so much for civil rights.

Now he could no longer stay silent.

MARTIN LUTHER KING: I come to this magnificent house of worship tonight because my conscience leaves me no other choice.

A time comes when silence is betrayal.

That time has come for us in relation to Vietnam.

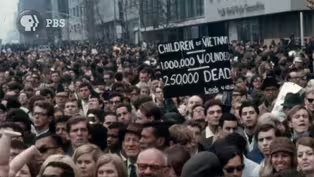

("Talking World War III Blues" by Bob Dylan playing) NARRATOR: Eleven days later, King joined Dr. Spock and perhaps half a million other protestors at a massive demonstration in Central Park organized by a new coalition, the National Mobilization to End the War in Vietnam.

♪ Some time ago a crazy dream came to me ♪ ♪ I dreamt I was walkin' into World War III.

♪ ZIMMERMAN: That was the biggest crowd any of us had ever been in in our lives.

And when the front of the march got down to the United Nations, the back of the march had not yet left Central Park.

That's how many people we were.

Not all of the people on that march were students.

And as a result, we all felt we have a chance now.

You know, there's a path that we could see to ending the war.

MARTIN LUTHER KING: Stop the bombing.

Let us save our national honor.

Stop the bombing, and stop the war.

Let us save American lives and Vietnamese lives.

Let us take a single instantaneous step to the peace table.

Stop the bombing.

NARRATOR: The antiwar movement was growing in numbers and militancy.

"We are no longer interested in merely protesting the war," one organizer said, "we are out to stop it."

Meanwhile, some in the Johnson administration became convinced the antiwar movement was a communist conspiracy directed by Moscow.

The FBI and the CIA, which was barred by statute from operating within the United States, began infiltrating the movement, wiretapping its leaders, even inciting violence in order to undercut their appeal.

ZIMMERMAN: At that time, people who supported the war were fond of saying, "My country right or wrong"; "America, love it or leave it."

Or "Better dead than Red."

Those sentiments seemed insane to us.

We don't want to live in a country that we're going to support whether it's right or wrong.

We want to live in a country that acts rightly and doesn't act wrongly.

And if our country isn't doing that, it needs to be corrected.

So we had a very different idea of patriotism.

So we began an era in which two groups of Americans, both thinking that they were acting patriotically, went to war with each other.

Over 200,000 communist sympathizers in that park this morning tried to burn this flag, but they didn't succeed.

RICHARD NIXON: I would put it this way-- there's a monstrous myth abroad, a myth which Hanoi creates and which it believes, and that is that the United States is so divided that if they just hang on that they will win in Washington, and in the United States the victory that our fighting men are denying them in field.

WESTMORELAND: As I have said before, in evaluating the enemy strategy it is evident to me that he believes our Achilles' heel is our resolve.

NARRATOR: Two weeks after the Manhattan protest, General Westmoreland addressed a joint session of Congress, the first general ever to be called home from a battlefield by his president to do so.

Backed at home by resolve, confidence, patience, determination, and continued support, we will prevail in Vietnam over the communist aggressor.

(applause) NARRATOR: Behind the scenes, neither Westmoreland nor the administration he served was confident the United States would prevail.

Westmoreland reported to the president that according to the latest statistics, the crossover point had finally been reached that spring, except in the military sector just south of the DMZ.

But, he warned, the United States was doing little better than holding its own.

If he were given 200,000 additional troops and allowed to go into Laos and Cambodia, he could cut off the Ho Chi Minh Trail and end the war in two years.

But "When we add divisions," Johnson asked, "can't the enemy add divisions?

Where does it all end?"

Westmoreland had no answer.

Instead, he and the Joint Chiefs asked the president to permit them to bomb sites just below the Chinese border, and to mine the harbors of North Vietnam to keep Hanoi's Soviet ally from resupplying her by sea.

Meanwhile, Robert McNamara, the chief architect of American strategy in Vietnam, had grown less and less confident in its ultimate success and in the repeated calls for more men and more bombing made by the military he oversaw.

GELB: Robert McNamara was the giant of Washington, D.C.

He was the embodiment of intellect and self-confidence.

If there was a problem, there had to be an answer.

And that was his fatal flaw.

The startling thing is that this man who never seemed to doubt anything he said, actually began to doubt profoundly what he was doing in Vietnam.

But we didn't know about it.

NARRATOR: In a private memorandum to the president, McNamara told Johnson that "the picture of the world's greatest superpower "killing or seriously injuring 1,000 non-combatants a week, "while trying to pound a tiny, backward nation into submission "on an issue whose merits are hotly disputed is not a pretty one."

He urged the president to limit troop levels, not raise them, and to declare an unconditional end to all bombing north of the 20th parallel.

"The war in Vietnam is acquiring a momentum of its own that must be stopped," McNamara wrote.

"Dramatic increases in U.S. troop deployments "and attacks on the North are not necessary "and are not the answer.

"The enemy can absorb them or counter them, "bogging us down further and risking even more serious escalation of the war."

In the end, Johnson tried to find a middle ground.

He expanded the list of bombing targets, but he refused to mine the harbors and he agreed to send Westmoreland only 47,000 more troops, which would bring the total of U.S. forces in the country to more than half a million men.

On June 17, 1967, Robert McNamara placed a call to his military assistant, Lieutenant Colonel Robert Gard.

GARD: My phone rang and the little light showed it was the secretary on the line.

And I picked it up and said, "Yes, Mr.

Secretary?"

And Mr. McNamara said, "Bob, I want a thorough study done of the background of our involvement in Vietnam," and hung up the phone.