Call The Doctor

Digestive Disorders

Season 35 Episode 11 | 27m 7sVideo has Closed Captions

We'll talk about common stomach & intestinal issues, when to worry and what you can do

We all get digestive issues from time to time. But there are those whose symptoms are much more severe than that. Some people deal with poor digestion every single day, and that can affect their lives in many different ways. We'll talk about some of the more common stomach and intestinal issues, when to worry and what you can do if this describes you or someone you know.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Call The Doctor is a local public television program presented by WVIA

Call The Doctor

Digestive Disorders

Season 35 Episode 11 | 27m 7sVideo has Closed Captions

We all get digestive issues from time to time. But there are those whose symptoms are much more severe than that. Some people deal with poor digestion every single day, and that can affect their lives in many different ways. We'll talk about some of the more common stomach and intestinal issues, when to worry and what you can do if this describes you or someone you know.

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Call The Doctor

Call The Doctor is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(bright music) - [Voiceover] The region's premier medical information program, "Call the Doctor."

- We all get digestive issues from time to time, but there are those whose symptoms are much more severe than that.

Some people deal with poor digestion every single day, and that can affect their lives in many different ways.

We'll talk about some of the more common stomach and intestinal issues, when to worry, and what you can do if this describes you or someone you know.

Digestive issues on this episode of "Call the Doctor."

Hello, welcome.

We're so glad you're with us for this season and this episode of "Call the Doctor."

Let's get right to tonight's panelists.

We have a full house tonight, and I love that.

I love when we have so many great minds here.

We can have a good discussion about digestive issues, unfortunately, but I know it's something that a lot of people deal with in this area, so I'm gonna get right to who you all are.

If you could tell me who you are and who you represent, where we can find you?

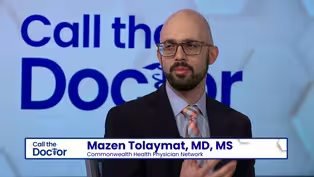

- Sure, I'm Dr. Mazen Tolaymat.

I'm a general gastroenterologist at Commonwealth Health, Wilkes-Barre General Hospital.

- Okay, welcome.

- Hi, I'm Aman Ali.

I'm a advanced gastroenterologist with Digestive Care Associates in Kingston.

- In Kingston, great, and welcome.

- I'm Dr. Charles Grad.

I practice with Lackawanna Medical Group in Scranton.

- All right, welcome to you.

And you, Sir?

- I'm Korta Yuasa, I'm a gastroenterologist at Geisinger Medical Center in Danville, and my interests are in Crohn's and ulcerative colitis.

- All right, great, we have a lot to get to tonight, so I think what we'll start with is the lack of a problem, basic function of the digestive system, when it's working, how it works.

I guess we'll start with you, Doctor.

How does it work?

Just sort of a boiled-down version of... Of I know there's a lotta different moving parts and pieces to a digestive system.

- Right, well, it's actually a lot, the map of the digestive system is a lot easier than one thinks.

So the digestive system starts in the oral cavity, in the mouth, esophagus, stomach, small intestine, and large intestine.

So from the mouth to the anal canal is the, I guess, the digestive system, start and finish.

The purpose of the oral cavity is to, obviously, you know, break down foods into smaller pieces, and the purpose of the esophagus is to transport the masticated material down into the stomach, where further churning and preparation for the liquid and solid components to be introduced into the small intestine, which actually does the majority of the absorption of calories and nutrients.

Which I think a lotta people don't know that.

Much of the digestion, as we know it, as we think it, takes place in 20 feet of small intestine.

Then the last five feet or so, the large intestine, its sole function, really, is to reclaim the water so that, in effect, we're making solid stool, or that's what we're supposed to be doing.

That's basically it, in 90 seconds.

- I mean I guess what I was getting at is there's a, there's a lot, there's a lot of different places where people could have issues in that entire system.

- [Dr. Yuasa] Mm hm.

How, we'll start with Dr. Grad.

How do you know when there's an issue and when... do you see what I'm getting at?

When do people - Right.

have to seek help?

- Well, the GI lab's about 30 feet long, okay?

20 feet of it's the small bowel.

Five feet is the upper intestine.

Five feet is the lower intestine.

Fortunately, okay, although he's an advanced endoscopist, fortunately most of the pathology is in the top five feet and the bottom five feet, which is fairly easily accessible with endoscopic equipment.

That's, you know, a large measure of what we do is upper GI problems, probably reflux is the most common.

Ulcers are less common now because of treatment for H. Pylori, but, you know, ulcers can occur from medications, too, but probably the most common upper GI problem is reflux.

Usually, it's benign, but it can be more serious.

Lower five feet, that's where there's a lot of action, okay?

And the biggest issue is the potential development of colon cancer, which gets everybody concerned, but also, inflammatory bowel disease involves predominantly the colon and, to some extent, the small bowel, too, with, especially, Crohn's, so.

- Could you explain what H. pylori is, to those who don't know?

- H. pylori is a bacterial infection that you acquire typically at an early age, and it's associated with the development of ulcer disease in the intestine and also, potentially, gastric cancer.

But you know there's, it used to be the idea that you know, people thought lots of things.

Food, if different issues and stuff like that.

And the person who first thought it might be a bacteria sort of got chuckled at, but it turned out to be an infection in the lining of the stomach that created ulcers.

- We'll get to you in a second.

I would love to know what some of the more common issues are that you hear of.

People in your office, what are they complaining of most often?

- Sure, as Dr. Grad already mentioned, you know, reflux, heartburn, is a common symptom we see.

Difficulty with swallowing, just with food getting stuck.

The other common things we will see is abdominal pain, diarrhea, sometimes blood in the stool.

We'll also see constipation.

Those are probably the most common things we see.

And then, a little bit less common would be issues with the liver.

Some liver diseases, for example, can cause jaundice, so which is yellowing of the eyes or skin.

So those are probably the most common things that I would see in clinic, and the reasons that patients would go to their primary care doctor, for example, or, sometimes, the emergency room and get referred to us is for further evaluation.

- I would imagine most people have issues from time to time.

You just don't feel great, something didn't sit well, et cetera.

Is there always an issue there?

Sometimes things just don't work as they should?

Or does that mean that there's something that's not working quite right?

- It's tough to say, 'cause, sometimes after we do some evaluation and we don't exactly find the answer, I think, a lot of these symptoms that last only for a short amount of time, you know you might be able to remember, oh I ate something that maybe wasn't so good or I got a stomach bug, or maybe my family member was sick and they passed on something to me, and sometimes we don't have a great explanation.

So a lot of times we see these patients and if the symptoms have already passed and everything looks okay then we maybe reassure them if we don't find anything serious.

And sometimes we do have obvious explanations.

It's when I think the symptoms become more chronic or certainly when they become debilitating or we see issues in the blood work or the patient's really struggling, that's when we become more concerned and we really wanna try to do a lot of evaluation to figure out what's going on.

- So we talked a little bit about the upper, and I know that you do a lot of those type of scopes, can you tell people what they might expect if they have to get one?

- Yeah, so the procedures we do to evaluation the gastrointestinal disorders, they, back in '60s or '70s when they were very simplified procedures of just doing a camera test down your throat when you're sedated and have an endoscopy done and or a colonoscopy done and from the bottom to look inside the colon.

But now we have really morphed into a much more complicated and advanced area, and can do a lot with the same platforms, you know, as we're going down the throat with endoscopy or EGD procedure, endoscopic esophago-gastro- duodenoscopy procedure, which is EGD, esophagus is E, G is the gastro, and duodenum is the upper part of the intestine, so the most common procedure we do is called EGD, and what you expect for EGD is patient will have overnight fast and they will come over to the endoscopy center or to the hospital where they're supposed to be.

Usually there are preoperative instructions given clearly as to what blood thinners they have to stop and what adjustment they have to make in certain medications, such as diabetes medicines and so forth.

And, essentially, what to expect is to get an IV in the pre-op area, explanation of the procedures, doctor will talk to you, explain what they're going to do, and then you go to the procedure room and from a patient perspective, they go to a sedation for this procedure most commonly, and that procedure itself takes about five to ten minutes to perform.

- It's that quick?

- Yes.

And what an endoscopist or what a doctor will do is that they will introduce a lighted instrument in patient's mouth carefully.

We have a mouth guard, which helps protect their teeth and protect the instrument.

And then we go carefully down the upper digestive tract into the esophagus, live looking at the anatomical structures in the esophagus and then into the critical area which we call GE junction here where the stomach and esophagus meets then we go in stomach, then we go in the intestine which is the duodenum, hence the EGD.

And, essentially, if we see anything abnormal we'll take biopsies, small pieces of tissue, very small, which are sent off for further analysis.

For colonoscopy, it is somewhat different.

Patients have to usually modify their diet the day before.

- [Julie] Mm hm.

- So they will be drinking only, what we call clear liquids.

And you know, soup and broth, and Jello, nothing red in color because that looks like blood to us.

And then they are given a cleansing agent, there are a variety of different cleansing agents, some are tablets, some are liquids, that they take to basically flush their system.

This is more medical proper cleansing, not the, not the colonics that you hear which is- - [Julie] Right.

- I'm just diverging here a little bit, but it has no medical value.

- [Julie] Okay.

- But anyway, so they cleanse and then after that you know, they will just come to the endoscopy suite the next day, just like for the endoscopy.

And they will be fasting over night and expect essentially the same protocol.

Colonoscopy takes a little bit longer, about 15-20 minutes.

- The biggest complaint is about the preparation, okay, and - Yeah.

You can modify to some extent with patients.

The biggest, and big change is I think has made colonoscopy much more satisfactory has been the sedation.

We grew up a lot with what we call conscious sedation which was Demerol, Versed and which kept the patient sedated but, you know, sometimes was more uncomfortable.

But there's major changes, major changes in colonoscopy and I think the biggest ones have been the anesthesia, which is Propofol, which is really just a fabulous drug for colonoscopies.

So that's been a huge, huge, huge benefit and just being able to complete the exam with the patient, you know, shows up in the recovery room and doesn't feel that anything's really been done.

And the other big thing that's changed to some extent especially in some of the hospital endoscopy areas are the use of CO2.

We don't put air into the colon.

A lot of people used to have a difficult time post colonoscopy with retention of air, cramping, discomfort, except you weren't sure if there was a problem.

Now, CO2 is infused into the colon and especially with protracted procedures as doctor does, okay.

It's been a huge, huge benefit so there's really no reason not to do a colonoscopy.

The prep is a little bit a problem for a day but the actual procedure and the potential of saving your life or removing a polyp before a surgeon has to take a large portion of your colon out, that's, it's a simple procedure.

It's hard to say how simple it is.

- How it is medically.

- I'd like to add one more - Sure.

- Improvement that we've made, we have an all male panel here.

- Yeah.

- But actually there are plenty of female gastroenterologists in practice now.

That is a big point of emphasis starting with our training.

We have a fellowship program, GI fellowship program and we have female candidates all the time.

I have excellent women colleagues in Danville and other areas, other sites.

So if that's an issue, that is definitely an option and the patient should inquire about that.

- [Julie] That's a good point.

- And ask their primary care doctors.

- [Julie] That's a very good point.

- Yeah, but women are actually more likely to get, in my mind, colonoscopies, they're used to mammographies, they're used to pelvic, they're used to, it's the men that - [Julie] (laughs softly) they always push the women first.

- [Julie] (laughing) - It's the wife that comes first, and she survives.

The guy will sometimes - [Julie] Then he goes in.

be pushed along.

- No but, with that, with that same, on the same note I would say that from patient perspective, because we have been on the other side of the table and from family members' standpoint when they went to procedure or our own personal experiences, procedure is the easiest part of it.

You go to the procedure room or pre-op area, you're getting your IV, you get your sedation, and then you don't even remember it happened.

It's a completely painless procedure.

You should not expect any discomfort after the procedure.

Obviously you don't work that day, for 24 hours after the sedation, it's not safe to work or do anything important but other than that there's no limitation from your life to life day to day activities, you can resume your function next day.

- I wanted to get into some of the specifics, some of the problems, and I'll start with you, Dr. Yuasa, because I know you deal a lot with Crohn's and and ulcerative colitis.

Could you explain.

- [Dr. Yuasa] Yes.

Are those autoimmune issues?

- [Dr. Yuasa] Yes they are.

They're generally regarded as autoimmune illnesses and they tend to run with other autoimmune illnesses as well and so, with, they fall under the umbrella of inflammatory bowel disease with a D, as opposed to IBS, which we can talk about later.

So Crohn's Disease can affect anywhere from the mouth to the anus, like I described earlier.

Ulcerative colitis is typically limited just to the large intestine, almost universally involving the rectum and spreading upward, so to speak, over time.

And the other thing about it is there's no really cure for either one of the diseases yet.

You know, that's an area of active research.

So we are tasked to treat the illness usually requiring immunosuppression at one point.

- [Julie] Mm hm.

- After a certain amount of time, usually, and they typically occur, they typically diagnose between the ages of 15 to 30, so it's predominantly a disease of younger people, people who are transitioning from school to work, from childhood to adulthood to parenthood.

So it's a, so these are people, autoimmune illnesses affecting people in the crossroads of life which I find very rewarding.

- And so those are two issues in particular that, I mean, anecdotally, I know a lot of people, or I seem to, who deal with those types of issues.

But you mentioned earlier that these are, this is not something you can take a pill for, this is not something you can just treat and fix, this is sort of a lifelong - [Dr. Yuasa] Yeah.

- partnership you're going to have to have with a doctor.

- [Dr. Yuasa] Yeah.

- What do you tell your patients?

- No, you're absolutely right.

So, you know, again just painting in broader strokes.

You know, this is an autoimmune illness, it's a chronic lifelong illness for now, we hope that there's a cure in the future.

But and there is no quick fix.

The treatment, for the most part, you know deals with somehow manipulating your immune system to dampen the immune system to stop it from attacking your own body.

And it's a lifelong process and so, there are no quick fixes.

And with Crohn's Disease, I should add, you know, some surgical things here, even though we're all medical doctors, so for Crohn's Disease, surgery is not a cure.

And so the viewers should know that.

There are times you need to have surgery because Crohn's Disease can develop into complications such as you know, intestinal obstructions, abcess formations, what have you, so it's not a cure.

With ulcerative colitis, interestingly enough, you can technically say, once you remove the large intestine a subtotal colectomy, that's potentially a cure, but a lot of times you trade it for other illnesses, - [Julie] Other things.

other conditions, which might cause, we can certainly talk about as well.

- Now that's IBD, different from IBS.

- Yeah.

- Right.

- But what does IBS even, I know what it stands for, but what does it even mean?

- So I guess the first thing is that the unfortunate fact that the acronym for IBS, or Irritable Bowel Syndrome, and IBD, Irritable Bowel Disease, are very close and so patients can often get confused because they're very different things.

And the other unfortunate part is we don't really 100% understand what IBS exactly is.

So it's probably the most common thing that any of us see in our clinics.

And often patients will come with abdominal pain, and either diarrhea or constipation, or both.

And we need to do a little bit of an investigation to make sure they don't have other common diseases such as Celiac or Crohn's Disease or things like that.

But there's no specific test they can say for sure you have IBS, but it's more like the the clinical history, what the patient tells us combined with the fact that we tested for other diseases and none of them came back positive.

And there's a lot of research into why people have IBS.

Probably in 50 to 100 years we'll understand it a lot better and it might turn out that it's actually several different things.

It might be the, part of our the nerves that control our gut some might be hyperreactive, it might have something to do with the bacteria that live in our colon and all of us have billions of bacteria that live in our colon, but some people might have different strains that might cause it.

This also means that, because we don't understand 100% why it happens, we don't understand exactly how to fix it.

And so, there's a couple different treatments we can try and different approaches, and it's not a one size fits all, you kind of have to work with the patient, and similar to IBD, it's really, for most people it's a chronic lifelong thing, where we kind of have to work with the patient, try different things and approach it really from a multitude of different areas, not just from their symptoms, but also we are beginning to understand that it might be related to the brain gut connection, because we have a lot of nerves that connect our brain to our gut.

And so sometimes some of the chemicals in our brain that make us feel happy or sad or stressed might go actually go down to our gut and give us some symptoms, so patients might feel that's strange but I also like to remind them that, you know, when you're nervous we have the saying that you have butterflies in your stomach.

So when you're nervous, you know there's nothing going on down here, but you kind of feel it through your gut.

So in the same way, IBS might be triggered by those things.

Certain emotions.

- [Julie] Oh.

Life stressors, it might be triggered by certain things you eat, we don't really 100% understand it, so there's not one size fits all, unfortunately for these.

But we kinda have to work with our patients, and sometimes it requires some trial and error to figure out what exactly worked with the patient and they have to kinda come back and see us really form a partnership when it comes to IBS.

- Some people have fairly severe IBS, either way, constipation, diarrhea, and there are medications, but it's still viewed as a benign disorder, so we've had, at least in my lifetime, several different medications, Propulsid, Cisapride, Zelnorm, that the pharmaceutical companies invested billions of dollars in developing the medication but since the disorder is a benign one, these meds became more popular out after initial testing and then there were some developments with cardiac issues and three incredibly wonderful drugs that dealt with receptors and dealt with the way the bowel works had to be pulled from the market because it's still a benign disease.

I mean, Crohn's and ulcerative colitis is not a benign disease.

You see the ads over and over again on television about the benefits and then you hear the possible complications but that's still a very serious disease so accepting some risk for those medications is acceptable, given the fact that the disease is a very serious one.

IBS is still viewed as benign, but for a lot of people, it's not a benign disorder.

- I was gonna say it's probably really hard to tell a patient who's really struggling- - [Dr. Grad] I, no, no, and there are medicines.

- Right.

You know, Lotronex was taken off the market but there was enough medication, enough of patients that were on the medicine and it was wonderful for 'em.

And they lobbied to the Congress to put it back on the market with restrictions.

So, you know, it's a situation where IBS, as we say, one of the more common things we see but you know, it's still a benign condition.

- I mean, it is a benign condition, but it could be debilitating for the patient.

- Sure.

So, um, - Yeah.

When we say benign, we know it's not going to cause mortality or, you know, their lifespan is not gonna be shortened by it, such as, for example, pancreatic cancer is a death sentence for some, some of the patients.

So, IBS, in that regard, is also labeled as functional disorders and the functionality of the gastrointestinal system is not well, and we have a host of functional disorders elsewhere in the GI tract as well, but what I find helpful and as my colleagues have mentioned that it is not one particular strategy that fits all, but patient empowerment, I believe, by education and letting them understand their disease state, the peaks and troughs that comes with it.

It's not going to be a steady state, and then really, sort of, you know, capturing this disease and taking control of the disease, understanding it and addressing the 600 pound gorilla in the room and, you know, letting the patient control the disease rather than disease control the patient.

So that, that is important.

But having said that, when needed, we, as the patient coach we will advise them, lifestyle modification, dietary modifications, as well as some medical pharmacological intervention, which can help some select patients significantly.

- Is there a hereditary component to some of these illnesses?

I mean, are you more likely to see them in families?

- Certainly, I mean, all across the spectrum in gastrointestinal disorders, you do see the family history plays a very important role.

Whether it be inflammatory bowel disease, whether it be some of the genetic syndromes, in terms of the cancers that are prevalent in a certain family population.

So, yes, definitely there's a component to that.

- And I suppose with the last few minutes we have we can get into, we've talked about some various issues in the digestive system, but I know you've all at some point brought up cancer, and the screening for cancer, you're seeing things a lot younger than you have?

I mean, I know that the recommendation has has gotten a little lower, Dr. Yuasa?

- Yes, so the colon cancer screening in general I think the recommendation is to start at 45.

Still say somewhere between 45 and 50, but for general, average-risk patients, so patients without, people without family history of colon cancer, usually defined as a first degree relative.

So, a sibling or parent, diagnosed with cancer before the age of 60 is considered to be the significant family history.

So, like, a grandparent really wouldn't count there.

So somebody without family history or somebody without ulcerative colitis or Crohn's Disease which can increase the risk for colon cancer, so those at average risk should start at 45.

Those with first degree relative with young colon cancer, you should start either at 35 or 10 years before the age of diagnosis for that index family member.

- [Julie] Mm hm.

- So if you have a dad that was diagnosed at age 57, you should start at, well, 45.

Or, it's 47 or 45, whichever's earlier, so if you have a father that was diagnosed at age 50, you know, you should start at 40, I guess is the better.

- If you have one of the, I'm sorry, go ahead.

You were gonna say something - I was just gonna add for the non-medical people watching, when we say screening and medicine we typically are talking about trying to find a disease before it causes symptoms.

So just for our viewers out there, you don't want to wait until you have symptoms, so this is saying if you have absolutely no symptoms and you reached the age of 45 and you have no family history we wanna try to find it before it starts or if, God forbid, you have it when it's still early before it causes symptoms 'cause then hopefully we can treat it or even prevent it.

- This is the one arena where it is actually preventable.

- Yes, and we screen for other cancers and your primary care doctor might screen you for Diabetes, for example, but screening just means that you don't have any symptoms of it yet, and we wanna try to catch it early.

- The other thing that we talked about was the Cologuard because you see an incredible number of ads regarding a Cologuard test, and the Cologuard test is a reasonable choice for average risk patients.

It's not actually for any high risk, they say that.

So, the issue with the Cologuard is it's every three years.

It's not like, if you have 45, no history, you get a colonoscopy, a good quality colonoscopy, the next time you're doing that is 10 years.

If you get a Cologuard, you're really supposed to repeat the Cologuard every three years.

Okay, so that, it's a big difference and we talked in terms of the, the false positives of, you know.

- [Julie] Right.

And then you get through, have to do the colonoscopy anyway, but it it, it does bring some people who just are terrified about the idea of getting a colonoscopy to do a Cologuard, and if then if it's positive, at least the data suggests that two thirds of them will then go in and get the, one third will still not do it.

- I hope if nothing else, someone gets a screening at least, from this show.

That's all the time we have, and that's gonna do it for this episode.

We're really glad you've joined us.

For all of us here at WVIA, I'm Julie Sidoni, we'll see you next time.

(soft bright music)

Clip: S35 Ep11 | 1m 49s | Charles T. Grad, MD - Lackawanna Medical Group (1m 49s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Explore scientific discoveries on television's most acclaimed science documentary series.

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

Call The Doctor is a local public television program presented by WVIA