Call The Doctor

Autoimmune Disease

Season 35 Episode 5 | 27m 13sVideo has Closed Captions

What happens when our body fights itself

A healthy immune system defends the body against disease and infection. But when that system malfunctions, the body mistakenly attacks itself. That’s autoimmune disease, and according to the National Institutes of Health – there are more than 80 of them!

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

Call The Doctor is a local public television program presented by WVIA

Call The Doctor

Autoimmune Disease

Season 35 Episode 5 | 27m 13sVideo has Closed Captions

A healthy immune system defends the body against disease and infection. But when that system malfunctions, the body mistakenly attacks itself. That’s autoimmune disease, and according to the National Institutes of Health – there are more than 80 of them!

Problems playing video? | Closed Captioning Feedback

How to Watch Call The Doctor

Call The Doctor is available to stream on pbs.org and the free PBS App, available on iPhone, Apple TV, Android TV, Android smartphones, Amazon Fire TV, Amazon Fire Tablet, Roku, Samsung Smart TV, and Vizio.

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship(gentle music) - [Announcer] The region's premier medical information program, "Call the Doctor."

- A healthy immune system defends the body against disease and infection.

But when that system malfunctions, the body mistakenly attacks itself.

That's autoimmune disease.

And according to the National Institute of Health, there are more than 80 of them.

What happens when our body fights itself, in this episode of "Call the Doctor."

Welcome, we are so glad you're with us for this episode of "Call the Doctor."

Let's get right to tonight's panelists.

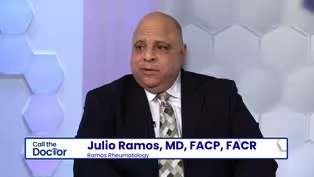

We have two doctors with us this evening, and I would love to start by just allowing you to tell us a little bit about who you are, and who you're representing here tonight, so Dr. Ramos, we'll start with you.

- Hi, I'm Julio Ramos, I'm president and CEO of Ramos Rheumatology locally here in Avoca, kind of born and raised here.

So I'm originally from Long Island, but I came to school to Kings College where I was a chief, I was captain of the shooting team there.

And came, did my residency here at the Scranton-Temple Residency Program in Scranton.

Did my fellowship training at Geisinger, and then I've been, since 2002, I've been in Scranton area.

- Welcome.

You pointed at this guy, you knew him from way back.

Hi, Dr. Pugliese.

- Yes, hi, I'm Dave Pugliese, I'm the, the Director of Rheumatology for Geisinger Health Systems.

I've been with Geisinger for 23 years now, So when Dr. Ramos did his fellowship there, we got to meet each other and interact for a little bit, so we kind of go back for a while, but I've been part of rheumatology with Geisinger for a long time, and we take care of all kinds of different autoimmune, rheumatologic conditions.

- Well, welcome to you both.

Let's get this out of the way first.

There's no possible way we're going to get through all autoimmune diseases in 25 minutes.

I understand that this is a giant, giant topic.

So we'll do our best just to whittle down the basics and what you would love people to take from this.

I'll start with just going way, the granular, what triggers this, all the way back to what causes this?

Do we know?

- No, the answer is, the short answer is no.

Autoimmune diseases are really a vast disorder, and we believe that it happens in genetically predisposed patients.

What is a predisposition?

Again, it could be genetics, but it could be environmental.

It's a hodge podge of things that something in a patient gets triggered, and the immune system just wakes up and starts attacking your body.

It feels that the body is not theirs, and it just keeps on attacking it as a foreign thing.

- [Sidoni] Tuning on itself almost.

- Exactly.

Mm-hmm.

- Can you name some of the more common autoimmune diseases?

- Sure.

There, there's a whole host of 'em, probably a whole bunch people have heard of.

I mean, most common ones that people will know, rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, psoriatic arthritis.

I mean, there's probably thousands if we were to go through the list.

But a whole host of different manifestations of autoimmune disease.

And what ultimately winds up determining the diagnosis is how the immune system decides to target the body.

So if it decides to target the skin, we may call it psoriasis or lupus, depending on how it does it.

If it decides to target the joints, we may call it rheumatoid arthritis, or psoriatic arthritis, or some other version of arthritis.

And it becomes complicated because the immune system's everywhere, it can hit any part of your body, and depending on how it reacts with you, is how we define the name that we put on the disorder.

- It's anecdotal, but I wonder if more people are paying attention to their immune systems after COVID.

You know, people probably didn't think much about their immune system until COVID-19, and now it's, I don't wanna say a buzzword, but people are talking about it.

Do you find that a lot of this has to do with educating your patients?

- I think so.

I think so.

And the fact is that we come back to arthritis, and arthritis is just one of these manifestations of autoimmune diseases.

There's about 130 different diseases that manifest with arthritis, which doesn't necessarily have to be an autoimmune disease.

But there's other diseases like thyroid disease is an autoimmune disease.

So, but I agree.

I think it, you know, you'll see it on TV more often where you see the commercials targeting the medications that we can use for the treatment of autoimmune diseases.

And then that brings it up to the patient's family and say, "Well, maybe I do have psoriasis, you know, and do I have psoriatic arthritis?

Let me talk to somebody about it."

And it, we spend a lot of our time educating patients about those diseases as well.

- Are there some auto, or you were gonna say something?

- Well, I think the COVID part is very interesting.

Part of what makes COVID very unique is it creates an immune response.

And so people who get very, very sick from COVID, it's not all the virus's fault.

Part of it is the immune system's fault.

And so in a lot of ways, COVID is actually an autoimmune disease.

And the challenges that we've had understanding who's gonna get sick with COVID, and who's gonna get common cold, and who's gonna get nothing, are the same kind of challenges we face with autoimmune disease.

We don't know whose immune system's gonna do what, but the people who get really sick from COVID, their immune system overreacts.

And in fact, we've in cases treated those COVID patients with rheumatologic medications to help control their immune system and try and prevent it from doing the damage that we see with COVID.

- It does seem like there's a relationship in many ways between viruses and autoimmune.

And that makes sense.

- So COVID is the trigger, COVID is the trigger in somebody that's predisposed in some way, be it, you know, obese people, or they have a predisposition to becoming very sick with something that is an insult.

- And possibly it would've just stayed there dormant all along, but something, you know, stressed out the immune system.

I mean, I'm, I'm asking, not telling of course, is that- - Yeah, that's absolutely right.

And what makes people feel sick when they get colds, viruses, bacteria, is not the cold, virus, or bacteria, it's the immune system.

So oftentimes there's a lot of challenge in figuring out, is your autoimmune problem just your immune system, or is there an underlying infection?

Because ultimately what happens with an autoimmune problem is your immune system's treating you like you have something infected, but you don't.

And then we have to tease that out, and figure out what the story is.

- If you have one, are you more likely to have others, or develop others?

- Yeah, I mean they, immunity is kind of a challenging process.

We see certain conditions that kind of piggyback with each other.

And it is not uncommon for a person who has one autoimmune problem to actually have another one develop, or a couple of them.

And, you know, part of the challenge in the conversation is, do you have four different things, or do you just have an immune system that's presenting in four different places?

And some of that's splitting hairs, but the reality is, yeah, people who have one autoimmune problem oftentimes can manifest with another.

- Do you see that as well?

- Yeah, the perfect example is the undifferentiated connective tissue disease patient, where you have vague symptomatology, but you haven't developed the true autoimmune disease that's gonna be fulminant.

So though they can develop, you know, when you have the undifferentiated patient, you may develop polymyositis, or lupus, or scleroderma, or there's different branches on that little, the trunk of autoimmune diseases.

So it's something that we often say to patients, "Well, you know, we're gonna see how you progress."

You know, and often we have to wait as we we're discussing, we deal, we're very comfortable in rheumatology with uncertainty.

We live in it, we flourish in it.

- I would like to talk about that a little more, 'cause I think that's an important message for people to hear.

You have both said that autoimmune illnesses, diseases, present a lot of diagnostic challenges and you often have to set up a relationship with your patients so that they can trust you through this arduous process in some cases.

So what are some of those diagnostic challenges?

- Uncertainty.

One of the most common manifestations of autoimmune disease is fatigue.

"Doc, I feel tired.

I can't go through life like this.

You know, I can't make it through the day.

And I tell patients, it's the first thing that comes you know, when you have an autoimmune disease, it's probably the last thing to go away if we treat it correctly.

Or it may never go away.

But it, there's a lot of uncertainties that we have to tease, and it's mainly a relationship with our patients.

I tell you know, my patients "I'm the one writing your story, you're telling it to me, but I'm writing it.

And together we'll find out what the, what the solution's gonna be."

But it has to be a relationship between the doctor and the patient.

- I think part of the big challenge with all this uncertainty is we have relatively poor tools to use to make diagnoses.

You know, nowadays, you know, medicine's evolved so much, and you know, a lot of people sort of feel like you should come in, you should get your test, and the test should tell you the answer.

You get your cholesterol checked, it's high, you get your medicine, it goes down and it's better.

In rheumatology, our labs are often fraught with false positives and false negatives, they're associated with lots of different conditions.

And so you come in and you say, I have these symptoms and I have these tests.

They may not match, the tests may be false positives, false negatives, and it becomes very murky water, and that's where the relationship comes in, helping to understand the truths of the testing we have, the balance of what are your symptoms, how do they match, how do we justify that you have this lab, or don't have this lab?

And a lot of times we make diagnoses, you know, sort of the old-fashioned way based on history and exam.

And it's sort of the hallmark of what we do in rheumatology is not the CAT scan and not the blood work, it's the history and the exam that tell the story, and we try to make everything else fit around that.

- What are some of the bigger misconceptions that you hear in your office?

- Probably the biggest misconception is that "I have lupus because I had the lupus test."

And the problem that brings that on is, you know, and it's nobody's fault, but in medical education, we don't get a lot of rheumatology training.

So we get taught that this certain test, this ANA, means lupus.

The reality is that an ANA doesn't mean lupus, it's at best a mediocre screening lab.

But you go to somebody who has not been a rheumatologist, and they check the lab, and they say, "Oh, your lupus test came back positive."

Now we see a person who says, "I've been told I have lupus."

And we have the challenge of making that person feel comfortable when we challenge that diagnosis, and challenge that lab, and try to reframe the story and say, "Okay, yeah, you have the lab, but this is actually what clinically it looks like."

- So you could possibly, I don't wanna say diagnose, but think it's one thing, and then a couple months down the road, another symptom pops up or another, whatever the case may be, and now suddenly you think it's a different thing.

Is that hard to get people to trust you sometimes?

- Yeah.

And, and the, I think the, the bigger diagnostic thing is the fact that some people come in and have normal lab tests.

- [Sidoni] Normal, completely normal.

- They feel miserable, they feel miserable.

And again, it's really listening to the story.

You know, they're stiff, they have sores in the mouth, they have ulcers, they have rash.

"But I have normal lab test doc, and it, it can't be in my head."

It's all in my head, and I've been to six different doctors and you know, but I feel sick.

And we have to tell patients that 20%, 20, of every five patients come to the office with a progressive rheumatologic or autoimmune disease, have normal lab tests.

So it's really up to us to really kind of tease out the story and, you know, get a plan together to get, hopefully, a better answer.

But that often that doesn't come in the first visit, either.

- And so sometimes the lab test, the flip side to that, is the lab test can be positive, and there's studies that show it can be positive for 10 years before anything ever happens related to that lab test.

So, you know, somebody comes in says, "I have a rheumatoid factor," and we say, "You don't have rheumatoid arthritis."

And that's a partnership.

You have to do that in such a way that they understand why you're saying that, they understand what the implications of the lab are, and so yeah, you have to always have that interaction to say, "We need to talk, we need to keep the conversation going, 'cause things are gonna change, your immune system's up and down, things are gonna evolve, and when they do, that's when we're gonna try to put the puzzle pieces together."

- But clinical findings could be deceiving as well.

So I'll give you an example of a patient comes in with a big swollen toe.

And they've been, you know, their uric acid level may be a little bit elevated, so here comes a story of a gout patient, right?

Well, psoriasis, psoriatic arthritis, can present with a big sausage-looking toe.

And because they're hypermetabolic, they can develop elevated uric acid.

So what seems to be gout, upon further discussion, you know, they have a family member with psoriasis.

So you have to tease out again, that story from that patient and say, well, "You actually don't have gout.

You have dactylitis, which is an autoimmune disease associated with psoriasis, involving the tendons, just looks just like gout."

- You mentioned family members.

So there's, is there a strong hereditary component to an autoimmune disease?

- There can be.

- There can be?

- It can be.

So the data shows that, you know, so if you have a family member with lupus, for example, so lupus happens in about 1-2% of general population, all of the world, right?

So if you have a family member with lupus, your risk for developing lupus is about 3%.

So there's a 97% chance that you will not have lupus, but there's a little bit higher chance.

So again, it's about listening to the whole entire story, and that includes your family history.

- It's also interesting that if mom or dad have autoimmune disease X, that increases your risk for any other autoimmune disease.

So if mom has lupus, that increases your risk for rheumatoid or some other autoimmune disease.

So it doesn't always draw straight lines, but family history plays a role, no matter what the diagnosis winds up being.

- You may not get that same autoimmune issue, but there could be that trigger latent there.

- [Dr. Pugliese] Yep.

- I heard you say something interesting about how many patients you see who feel like maybe it's all in their head.

How often does that happen if you have that test, that blood test or the diagnostic test that says nothing's wrong here, I don't see anything.

How often do you have to counsel patients through that?

- Every day.

- Every Day.

- Every day.

- Yeah.

- It's a difficult, - particularly for patients, because, again, these patients have seen six different specialists, and you know, they've seen the physical therapist, they've seen the chiropractor, they've, you know, seen, and plus they've also seen, you know, their friends who've diagnosed them through Google, you know, and they come in with what they feel the answer is because of what everybody else has told them.

But then there's a context that we have perspective on because we do this every day.

So I tell 'em, you know, I've seen you eight times today.

You know, and I also tell them that, you know, they're in the hole, and they're not looking up because the light is up there, They're here seeing, they're not seeing the light at the end of the tunnel.

But because of our 20 years of experience, we're already seeing the light at the tunnel many, many of these times.

So again, it's teasing out those, those uncertainties and you know, I mean, I'd be sick and tired of feeling sick and tired as well.

- [Sidoni] Sure.

- And, if you read about, you know, a lot of these conditions, there are data that show that it may take up to 10 years for people to arrive at a diagnosis.

So you can imagine what those 10 years are like, where you feel poorly, and you keep going to people, and saying, "I feel poorly."

And they keep saying, "I don't find anything in your labs, you don't have anything."

So there's a lot of frustration.

There's a lot of "People keep telling me I'm making it up, it's in my head, I'm struggling for no apparent reason."

And part of that is just the immune system doesn't declare itself very well.

And we have to, you know, be good investigators, we have to be patient, we have to be partners.

And sometimes it does take, you know, years to put the name on it.

You have to have a high index of clinical suspicion, you have to be really willing to listen to a person and their story, and put some faith in that, and, you know, work together.

But it can be a very challenging for patients to go through this.

- I'll add to that.

And it's, you know, you, there's, there's a character of a, of an elephant where somebody's looking at the tail.

So you see the neurologist, they're only looking at the nerve.

You know, we have the advantage of one, seeing those patients with all the data.

So we see the holistic approach of the patient.

So, we'll, we'll go back and dig down to the labs.

We'll see, you know, if I have a patient that has gone to Geisinger, so I can pull all those records.

So if you ask my family, they'll see me reviewing charts 'til like 11:00 at night because I want to see what's going on before I go into, because I know it's gonna be a difficult talk.

So we're seeing, we're seeing the bird's eye view, whereas when they see a lot of the specialists, they're, you know, the ENT doctor is seeing the nose, the neurologist is seeing the leg, you know?

So we're putting those pieces together as rheumatologists.

So we look great, because we have a lot of the information already.

- The benefit of seeing what- - Hindsight.

- The other, right, specialists have come up with.

What role does inflammation play, and is there a way to, for people to cut inflammation, or is there a way to stop inflammation, or cut it out somehow?

- So the hallmark of an autoimmune disease is inflammation.

Essentially what happens is, your immune system is doing to you what it thinks it ought to do for an infection.

And what it does is create inflammation.

If you envision cutting your hand, it gets red, hot, swollen, you know, and sometimes there's pus that comes out.

All that is inflammation.

Your immune system is coming at it, trying to kill the bacteria, the virus, whatever's in there.

That's what generates the pain, the swelling, the discomfort, et cetera.

In an autoimmune problem, your immune system has gotten confused and decides, all right, you know, I think this joint or this skin or this lung, or this whatever, is an infection.

And so it creates inflammation to try and fix that.

The problem is it's part of you, and it's not really supposed to be fixed.

So the inflammation is what manifests the symptoms.

What we wind up doing when we try to fix this, is trying to create a balance of controlling the inflammation without over suppressing the immune system, to open the door for the things the immune system's supposed to be preventing.

And that becomes a tricky situation where you've got lots of factors that you have to manage in, you know, infections versus disease, et cetera, so.

- So our job as rheumatologists is not to wipe out the immune system.

You know, I had this conversation with a patient, you know, today, where like, well, you know, you're giving me this medication, "You're taking my immune system away."

And I say, "Oh, that's not what we do."

We damper the immune system.

So we're kind of holding it down, just so you can function better without it attacking you again.

So we're not, and there's, you know, we call it cytokines.

There's all these proteins that float around in your body, and that's what we trigger, that's what we target when we treat patients with rheumatologic diseases, and pretty much all other autoimmune diseases.

We just have certain cytokines that we target for rheumatoid arthritis, or we target certain cytokines for lupus, or we target certain cytokines, but we're not at the time in our lives, and hopefully when my son becomes a physician, he'll find out that, okay, you have rheumatoid arthritis, you have this type of rheumatoid arthritis, this medication works well for this type of rheumatoid, and so we are gonna treat you with this.

For example, cancer, you know, you have small cell cancer, there's studies that show that this combination works very well for this type.

We're not there yet.

We're saying, "We're gonna give you this, hopefully it's gonna calm things down, but if not, we'll give it three months, we'll try something else."

And, that creates a lot of uncertainty for patients, because they're like, well, "Do you really know what you're doing?"

- And I'm sure medication, I mean, treatment of this has to be, that's another whole, that's another entire panel, right?

Because there's so many different kinds.

You had said earlier that treatment-wise, it's really all kind of a best guess.

- It is.

I mean, we're sophisticated enough to know the principles of how the immune system works.

We know that the, you know, white blood cells are coming in, they're spitting out these proteins that are the communication factors that pull in inflammation and create the problem.

What we don't know is which one of those proteins that are being called out is the one working in your body, versus the person who's got the same condition next to you, or whatever the scenario is.

You know, everybody may look the same from their clinical manifestation, but inside we have no way of knowing which one of those, you know, drivers is the right one.

And all these studies that we have show good success.

But you know, if you look at the data, they all show somewhere around, you know, 70% get a good response, and even as you get to great responses, those numbers get lower.

But that means every drug we throw at you could potentially have a 30% chance or more of doing nothing.

And you know, that's the conversation you have to have right up front.

Here's why we're picking it, here's what might happen, here's what might not happen.

- Is the drug, though, specific to the autoimmune illness, or does it really not matter if it's your immune system that is wonky, for lack of a better term, will the same drugs treat lots of different autoimmune illnesses?

- Yeah.

Again, but there's data.

So there's certain medications that we know work best for one disease process.

We do have some generic medications we call conventional disease modifying agents that we use for a whole platitude of diseases.

So methotrexate, for example, is something that we use for lupus, Sjogren's, you know, rheumatoid, psoriatic.

So we are, so we have some that work, but then there are some that are FDA approved only for the use of certain disease processes.

Maybe they'll work for lupus, but we can't use them for lupus because they're not, we're not allowed to, because they're not FDA approved.

But we bas...

In the old, you know, rheumatologic world, we used to put patients on bedrest, wrapping with blankets, give them aspirin until their ears rang.

Like really barbaric things, you know.

Bleeding was a treatment for rheumatologic diseases.

- [Sidoni] Wow.

And, but we've come a long way.

- And I think what's interesting about the medicines is, you know, this whole class of new class of medicines, these biologics that we use, they're the things that are on TV all the time, and, you know, everybody looks happy running around the yard with their family, and what what's really interesting, is at the evolution of these drugs, they get studied for one disease.

And some of the older ones, if you watch the time progression, they started out being approved for one, and some of them now are approved for, you know, 5, 6, 7, 8 diseases, because over time, as we've seen them work, and we've seen them in different settings, and we've studied them differently, we're understanding they may do more than one thing.

And we're relatively young in this field, so a lot of this stuff does translate from one to the other, depending upon what the condition is, what the drug is.

And you know, the flip side happens, too.

Sometimes they make one autoimmune problem worse.

So it becomes really a complicated scenario.

- And in saying that, I think one, something that we have to make sure that people know is that our job is not only to try to help people feel better, but our main job is to make sure that we balance the risks and benefits of these medications.

- [Sidoni] Of the medications as well.

- These medications can be extremely toxic, depending on, you know, what you're using it for, and what medication it is.

So our job is to, one, make sure that we're following these patients relatively often, doing lab tests, make sure we're looking, teasing out the medication related side-effects versus the benefits.

- Thank you, thank you to both of you.

This has been a fascinating conversation, and I wish we had some more time, but unfortunately that's gonna do it for this episode.

We're really glad you joined us.

For all of us here at WVIA, I'm Julie Sidoni, and we'll see you next time.

(gentle music)

Clip: S35 Ep5 | 42s | Julio Ramos, MD, FACP, FACR - Ramos Rheumatology (42s)

Providing Support for PBS.org

Learn Moreabout PBS online sponsorship

- Science and Nature

Explore scientific discoveries on television's most acclaimed science documentary series.

- Science and Nature

Capturing the splendor of the natural world, from the African plains to the Antarctic ice.

Support for PBS provided by:

Call The Doctor is a local public television program presented by WVIA